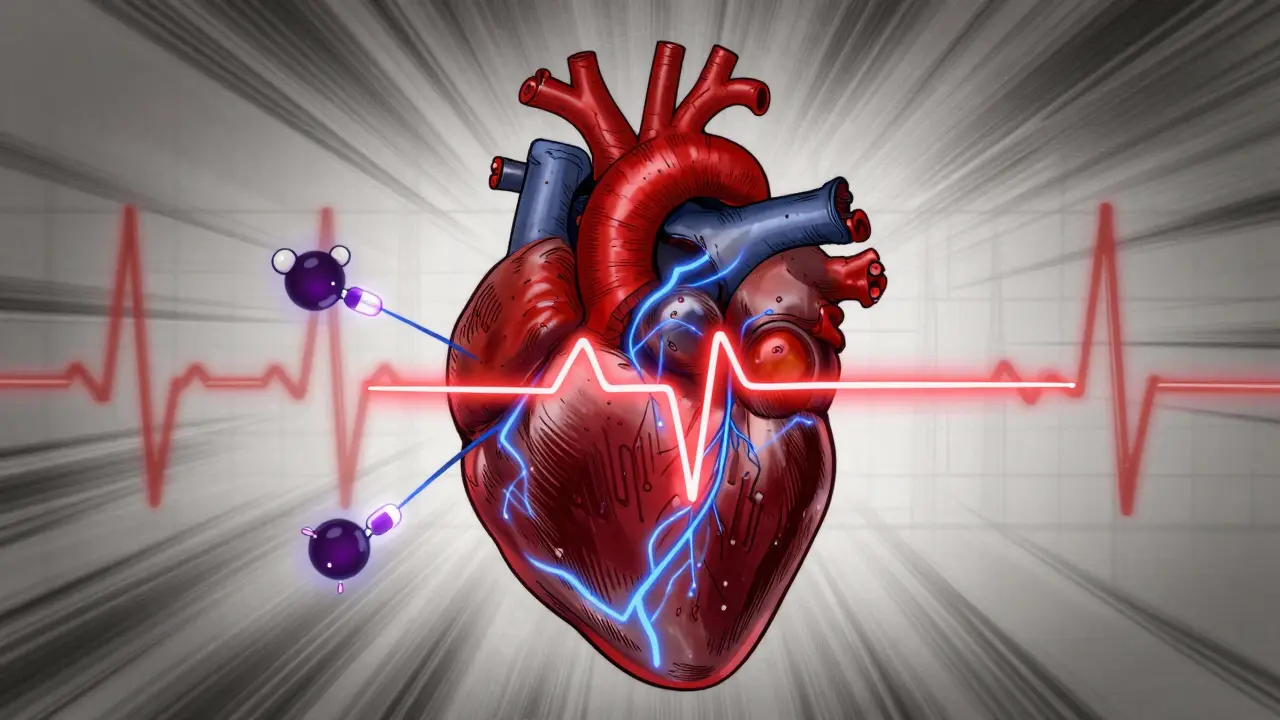

When your heart beats, it follows a precise electrical pattern. That pattern shows up on an ECG as waves and intervals - one of the most important being the QT interval. It’s the time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave, representing how long it takes your heart’s lower chambers to recharge after each beat. When this interval gets too long - a condition called QT prolongation - it doesn’t just look odd on a reading. It can trigger a dangerous, sometimes deadly, heart rhythm called torsades de pointes.

What QT Prolongation Really Means

QT prolongation isn’t a disease by itself. It’s a warning sign. It means your heart muscle is taking longer than it should to reset electrically after a contraction. That delay creates a window where the heart can misfire, leading to chaotic, uncoordinated beats. The most feared outcome is torsades de pointes - a twisting pattern of ventricular tachycardia that can collapse into ventricular fibrillation and cause sudden cardiac arrest. The risk isn’t theoretical. In 2013, the U.S. FDA reviewed 205 drugs and found 46 of them - nearly one in five - could reliably prolong the QT interval. By 2018, crediblemeds.org listed over 220 medications with known, possible, or conditional links to this risk. Many of these aren’t heart drugs. They’re antibiotics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, even anti-nausea pills.How Drugs Cause QT Prolongation

At the heart of this problem is a single ion channel: the hERG potassium channel. Found in heart cells, it’s responsible for letting potassium flow out during repolarization - the critical reset phase after a heartbeat. When certain drugs block this channel, potassium can’t escape fast enough. The result? The electrical signal lingers, the QT interval stretches, and the risk of dangerous rhythms climbs. The drugs that do this most often target the hERG channel because of their chemical structure. It’s not always intentional. Some drugs were never meant to affect the heart - but their molecular shape just happens to fit the channel like a key in a lock. Others, like sotalol or amiodarone, are designed to prolong repolarization to treat arrhythmias. But even these therapeutic tools carry a paradoxical risk: the very mechanism that stops one dangerous rhythm can trigger another.High-Risk Medications You Need to Know

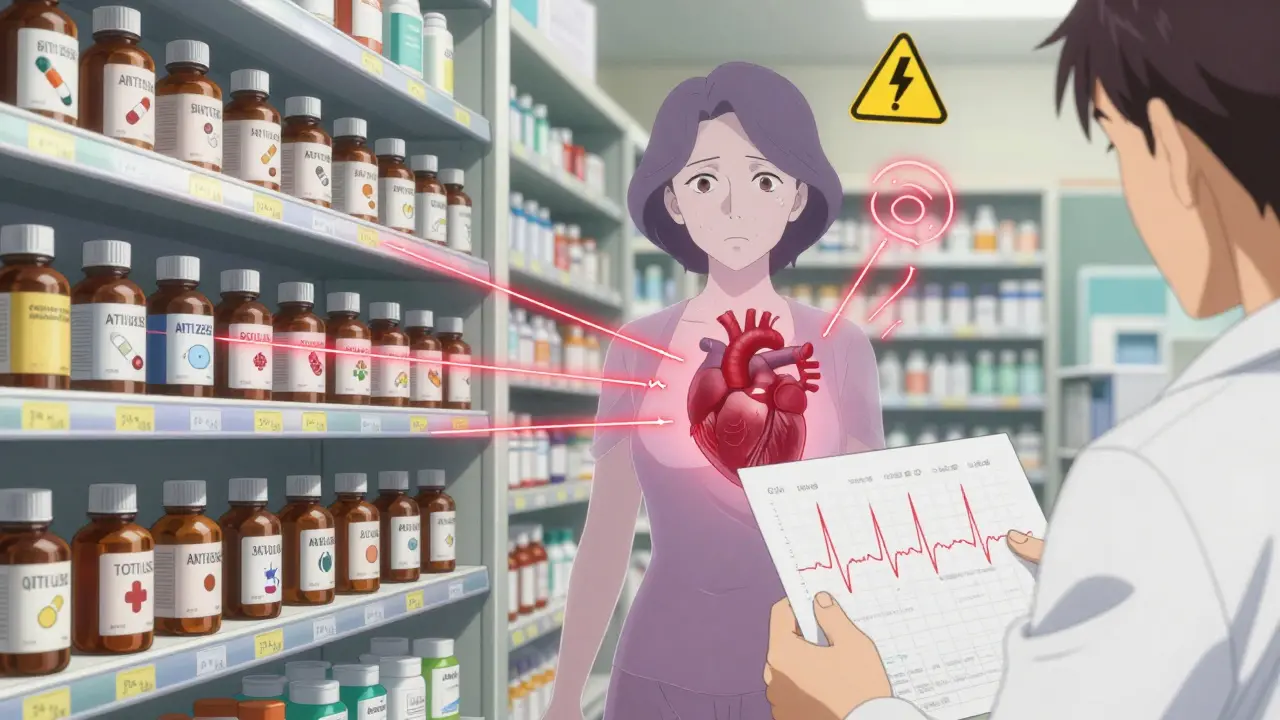

Not all QT-prolonging drugs are created equal. Some carry a much higher risk than others.- Class Ia antiarrhythmics - quinidine and procainamide - are among the most dangerous. Quinidine alone caused torsades in about 6% of patients in older trials.

- Class III antiarrhythmics - sotalol, dofetilide, ibutilide - are built to prolong QT, but sotalol has a higher TdP rate (2-5%) than amiodarone (under 1%), despite both blocking hERG. Why? Amiodarone blocks multiple channels, which stabilizes the heart more.

- Antibiotics - erythromycin and clarithromycin - can prolong QT by 15-25 ms, especially when taken with drugs that slow their breakdown, like grapefruit juice or certain antifungals.

- Antipsychotics - haloperidol and ziprasidone - have black box warnings for arrhythmia risk. Ziprasidone’s label specifically mentions sudden cardiac death.

- Antiemetics - ondansetron - is one of the most common culprits in reported cases. In one study, it appeared in 42% of TdP cases linked to drug interactions.

- Antidepressants - citalopram - led the FDA to cap its daily dose at 40 mg (20 mg for those over 60) after clear evidence of dose-dependent QT prolongation.

- Methadone - used for pain and opioid addiction - carries significant risk above 100 mg daily. Cases of TdP have been documented even in patients without other risk factors.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it. Women are far more vulnerable. Around 70% of documented torsades cases occur in women, especially after menopause or in the postpartum period. Their hearts naturally have longer QT intervals, and hormonal changes can make them more sensitive to hERG blockade. Age matters too. People over 65 are at higher risk due to slower drug metabolism and more frequent use of multiple medications. Those with heart disease, low potassium or magnesium, or a history of arrhythmias are also at greater risk. Genetics play a hidden role. About 30% of drug-induced torsades cases happen in people with subtle genetic variants in the hERG channel - variants so mild they’d never show up on routine testing. These people might take a normal dose of a drug and still develop TdP, while others with the same dose don’t.When Does QT Prolongation Become Dangerous?

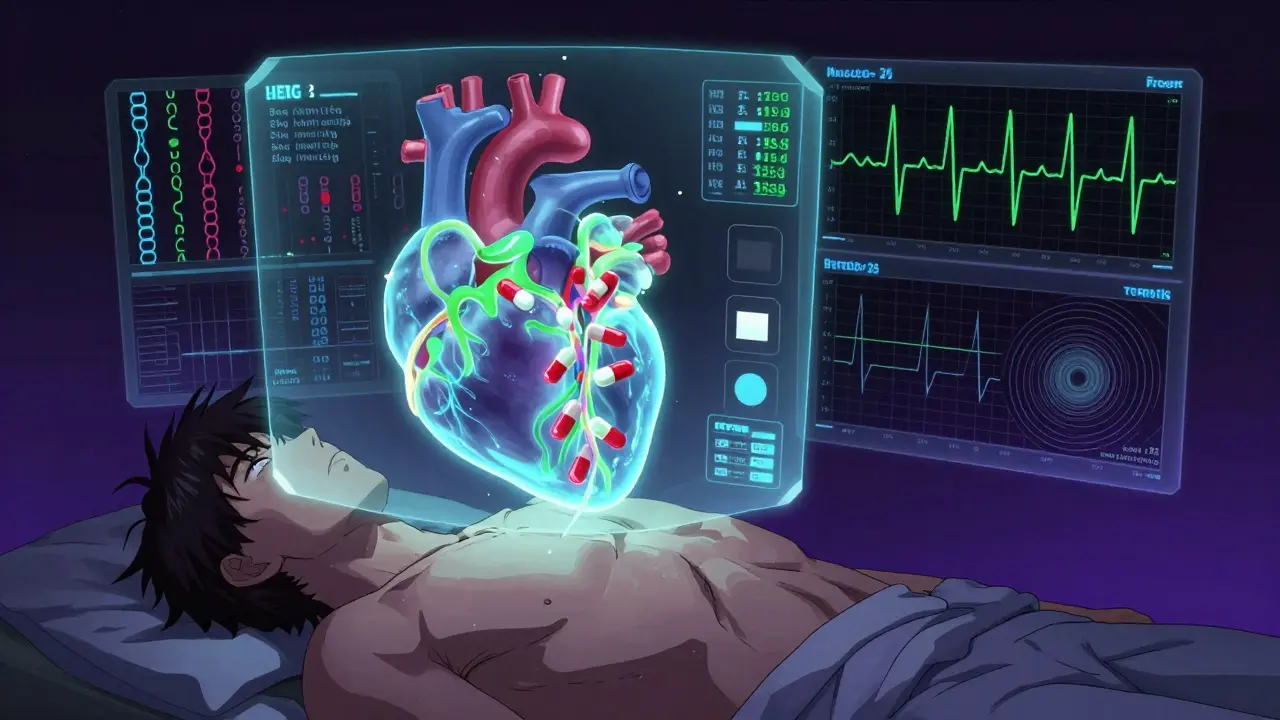

There’s no single number that guarantees danger - but there are clear red flags. - A QTc (corrected QT) over 500 milliseconds is a major warning. Studies show the risk of torsades jumps 3 to 5 times at this level. - An increase of more than 60 milliseconds from a person’s baseline QTc is also a strong signal to stop or adjust the drug, even if the absolute value is below 500 ms. The correction method matters. Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT / √RR) is the most common, but it overcorrects at slow heart rates and undercorrects at fast ones. Many hospitals now use Fridericia’s formula (QTc = QT / ∛RR) for better accuracy, especially in elderly or sedentary patients.Drug Combinations Are the Silent Killer

The biggest danger isn’t one drug - it’s two or more together. A 2020 analysis of FDA reports found that 68% of torsades cases involved multiple QT-prolonging drugs. Common combinations include:- Ondansetron + azithromycin

- Haloperidol + ondansetron

- Citalopram + clarithromycin

- Methadone + fluconazole

What Should You Do?

If you’re prescribed a new medication, ask these questions:- Is this drug on the crediblemeds.org list? (It’s free, updated quarterly, and used by hospitals worldwide.)

- Am I taking any other drugs that could interact?

- Do I have low potassium, heart disease, or a family history of sudden cardiac death?

- Should I get a baseline ECG before starting?

- Check electrolytes before starting.

- Get a baseline ECG - especially if you’re over 65, female, or on multiple QT-prolonging drugs.

- Repeat the ECG within 3-7 days after starting or increasing the dose.

- Stop the drug if QTc exceeds 500 ms or increases by more than 60 ms from baseline - unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk.

Juan Reibelo

January 24, 2026Wow. This is one of those posts that makes you realize how little you actually know about what’s in your medicine cabinet. I had no idea ondansetron could be this dangerous-my mom took it after chemo for years. I’m going to ask her doctor for an ECG this week.

Also, crediblemeds.org is now bookmarked. Thanks for the clarity.

Gina Beard

January 25, 2026Medication is a silent war inside the body. Most people never see the battlefield.

Josh McEvoy

January 27, 2026so like… my anxiety med + antibiotics + that nausea pill after sushi = cardiac roulette??? 🤯🤯🤯

why is no one talking about this in the grocery store???

Heather McCubbin

January 29, 2026They don't warn you because they want you dependent. Big Pharma doesn't care if you live or die as long as you keep buying pills. You think they want you healthy? Nah. They want you on 7 meds for life. Wake up.

And yes I know I'm being dramatic. But so is the system.

Tiffany Wagner

January 30, 2026I’m a nurse and this is so accurate. We had a patient last month-68, on methadone and fluconazole, no history of heart issues. Baseline QT was 420. Five days later, 530. She coded in the bathroom.

We didn’t catch it because no one checked. Just another Tuesday.

Thank you for posting this. I’m sharing it with my team.

Darren Links

February 1, 2026Wow. So now we’re just supposed to avoid every drug that isn’t aspirin? What’s next? Are we gonna ban all medicine because some of it can kill you? That’s not prevention, that’s fearmongering.

Also, why are you blaming doctors? They’re not mind readers. They don’t know you took that random antibiotic from your cousin’s prescription last week.

Maybe stop panicking and start taking responsibility for your own health?

Kevin Waters

February 1, 2026Just want to add something practical: if you're on any of these meds, get your potassium and magnesium levels checked. Low levels make QT prolongation way worse. I’ve seen patients with borderline QT values suddenly spike after a bad diet or a bout of diarrhea.

Also-yes, ask your pharmacist. They’re the unsung heroes of medication safety. Most of them know the drug interactions better than the prescriber.

And if you’re over 60? Get that baseline ECG. It takes 5 minutes. Could save your life.

Jamie Hooper

February 1, 2026bruh i took zpack + zofran after my flu last year and felt weird for a day… thought it was just the virus

so like… am i dead? 😅

jk but also not jk. i’m getting an ekg next week.

Husain Atther

February 2, 2026This is an excellent and well-researched summary. Many patients are unaware that even common medications can carry such hidden risks. In India, antibiotic use is often self-directed, and ECGs are rarely considered unless symptoms are severe. Awareness must be expanded beyond Western medical circles.

Thank you for highlighting crediblemeds.org-it is a vital resource that should be more widely known.

siva lingam

February 3, 2026so drugs can kill you. shocker.

Shelby Marcel

February 5, 2026wait so if i take citalopram and then eat grapefruit… is that like… a death combo??

also why does no one talk about this?? i feel like i just found out the government is hiding the truth about my antidepressants 😭