Most people assume lupus is something you’re born with - a lifelong autoimmune condition that strikes without warning. But what if your symptoms came from a pill you’ve been taking for years? That’s the reality of drug-induced lupus. It’s not rare. It’s not mysterious. And most importantly - it’s reversible.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced Lupus?

Drug-induced lupus (DIL) happens when certain medications trick your immune system into attacking your own tissues. The result? Symptoms that look exactly like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): joint pain, fatigue, fever, chest discomfort. But here’s the key difference - DIL doesn’t stick around. Once you stop the drug, your body usually resets itself.

First noticed in the 1950s in patients taking hydralazine for high blood pressure, DIL has since been linked to over 40 medications. The most common culprits? Hydralazine, procainamide, minocycline, and TNF-alpha inhibitors like infliximab. These aren’t obscure drugs - they’re used daily for hypertension, heart rhythm problems, acne, and autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

Unlike classic lupus, which mostly affects women between 15 and 45, DIL hits men and women equally - and usually after age 50. About 80% of cases occur in people over 50. And while SLE often damages kidneys or the brain, DIL rarely does. That’s a major clue doctors use to tell them apart.

What Symptoms Should You Watch For?

If you’ve been on one of these medications for months - or years - and suddenly feel off, pay attention. The signs of DIL are subtle at first but build up over time.

- Joint and muscle pain - This is the most common symptom. Up to 85% of people with DIL report achy, swollen joints - often mistaken for arthritis or aging.

- Constant fatigue - Not just tired. Exhausted. Even after a full night’s sleep.

- Fever without infection - Low-grade fevers that come and go, with no cough, sore throat, or other signs of illness.

- Chest pain or shortness of breath - This isn’t heart disease. It’s inflammation around the heart (pericarditis) or lungs (pleuritis). It hurts when you breathe deeply.

- Weight loss - Unexplained, not from dieting.

Here’s what you won’t typically see with DIL: the butterfly-shaped rash across the nose and cheeks (malar rash), severe kidney problems, seizures, or strokes. These are hallmarks of SLE - not DIL. If you have those, it’s likely something else.

One patient in Melbourne, 62, started on hydralazine for high blood pressure in 2021. By mid-2023, she couldn’t climb stairs without stopping. Her hands were stiff. She had fevers every other week. Her GP thought it was fibromyalgia. It took three visits to a rheumatologist before someone asked: “What meds are you on?”

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single test for DIL. Diagnosis is a puzzle - and your medication history is the most important piece.

Doctors start by ruling out other causes. Then they look for three things:

- Timing - Symptoms usually appear after 3 to 6 months of taking the drug. But they can show up as early as 3 weeks or as late as 2 years. If your symptoms started shortly after starting a new med, that’s a red flag.

- Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) - Over 95% of DIL patients test positive for ANA. But so do many healthy people. That’s why this test alone isn’t enough.

- Anti-histone antibodies - This is the real giveaway. About 75-90% of DIL patients have these. In classic lupus? Only 50-70% do. If your ANA is positive and your anti-histone test is too - especially if you’re on hydralazine or procainamide - DIL is very likely.

Anti-dsDNA antibodies? Those are common in SLE but rare in DIL. If you have high anti-dsDNA, your doctor will dig deeper. Blood tests for ESR and CRP will show inflammation - but they’re not specific to DIL. They just confirm something’s wrong.

Some doctors now check for genetic markers too. If you’re a “slow acetylator” (a genetic trait affecting how your body breaks down drugs), your risk of DIL from hydralazine jumps nearly fivefold. This isn’t routine yet - but it’s becoming more common in Europe and Australia.

What Happens When You Stop the Drug?

This is the good news: DIL usually goes away. Fast.

Once the triggering drug is stopped, symptoms begin to fade. Most people notice improvement within 2 to 4 weeks. By 12 weeks, 95% of patients are significantly better - often completely back to normal.

Here’s what recovery looks like in real life:

- 80% of patients feel 80% better within 4 weeks of stopping the drug.

- 60-70% only need NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen to manage lingering joint pain.

- 15-20% need a short course of low-dose steroids (like prednisone, 5-10 mg daily) for a few weeks.

- Less than 5% have symptoms that drag on longer - usually because they didn’t stop the drug early enough, or they were on multiple risky medications.

One Reddit user, after stopping minocycline for acne, saw his swollen knees disappear in 3 weeks. Another, who’d been on hydralazine for 18 months, said his energy returned “like a light switch turning on” after quitting the pill.

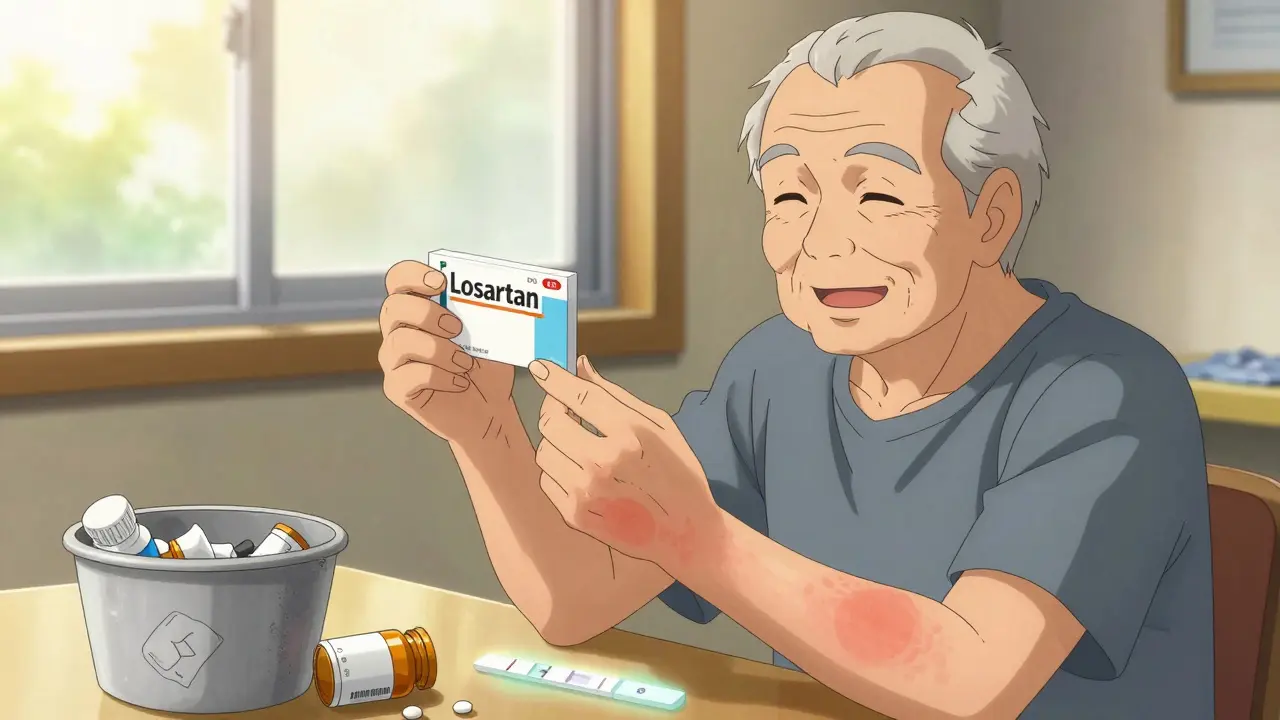

But here’s the catch: you can’t just stop these drugs on your own. Hydralazine controls blood pressure. Procainamide keeps your heart beating right. Stopping suddenly can be dangerous. Your doctor needs to switch you to a safer alternative - like amiodarone instead of procainamide, or losartan instead of hydralazine.

Which Medications Are Most Likely to Cause It?

Not all drugs carry the same risk. Some are rare triggers. Others are well-known.

| Medication | Typical Use | DIL Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Procainamide | Heart rhythm disorder | Up to 30% after long-term use |

| Hydralazine | High blood pressure | 5-10% |

| Minocycline | Acne, rosacea | 1-3% |

| TNF-alpha inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab) | Rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s | 1-3% |

| Isotretinoin | Severe acne | Rare |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab) | Cancer immunotherapy | 1.5-2% |

Procainamide is the biggest offender - one in three long-term users may develop DIL. That’s why it’s rarely used today unless absolutely necessary. Hydralazine is still common, especially in older adults, but many doctors now avoid it unless other options fail.

Minocycline, often prescribed for acne, is a sneaky one. People take it for months without thinking twice. But if you’re over 50 and develop joint pain while on minocycline - stop and ask your doctor. Switching to doxycycline often clears it up.

Newer cancer drugs like pembrolizumab are now being linked to DIL. This is a growing concern as immunotherapy becomes more widespread.

Why Do Some People Get It and Others Don’t?

It’s not random. Genetics play a big role.

If you’re a “slow acetylator” - meaning your liver processes certain drugs slowly - you’re at much higher risk. This is especially true for hydralazine. People with this trait have nearly five times the chance of developing DIL. The gene involved is called NAT2. Testing for it isn’t standard in Australia yet, but it’s recommended in parts of Europe before prescribing hydralazine.

Another factor? Age. Your immune system changes as you get older. It’s more likely to misfire. That’s why DIL is so rare under 40 and so common after 50.

And yes - women get it just as often as men. That’s different from classic lupus, where women are 9 times more likely to be affected. DIL doesn’t care about gender. It cares about drugs, time, and genes.

What If It Doesn’t Go Away?

Most cases resolve. But if symptoms linger after 3-4 months of stopping the drug, your doctor needs to investigate further.

Possible reasons:

- You were on the drug too long - damage started before you stopped.

- You’re still taking another trigger - maybe you switched one drug but kept another.

- You actually have early SLE - and DIL was just the first sign.

In rare cases, doctors may need to use low-dose steroids or even immunosuppressants like azathioprine. But this is the exception, not the rule. The goal is always to avoid long-term immune suppression if possible.

One study found that 25% of DIL cases are misdiagnosed as SLE - leading to unnecessary lifelong treatment. That’s why getting the right diagnosis matters.

How to Protect Yourself

If you’re on any of these medications - especially if you’re over 50 - here’s what to do:

- Know your meds. Keep a list - including doses and start dates.

- Don’t ignore new joint pain, fatigue, or unexplained fevers.

- Ask your doctor: “Could this be drug-induced?”

- Don’t stop your meds without medical advice.

- Request anti-histone antibody testing if ANA is positive and you’re on a high-risk drug.

And if you’ve been told you have lupus - but you’re over 50, male, and on hydralazine or minocycline - get a second opinion. You might not have lupus at all. You might just have a drug reaction.

What’s Next for DIL?

Doctors are getting better at spotting it. New guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology (2023) now include specific criteria for DIL diagnosis - including medication exposure timelines and antibody patterns.

Research is also looking at ways to predict who’s at risk before they even get sick. Blood tests for microRNA markers are in early trials. Genetic screening for NAT2 status could become routine before prescribing high-risk drugs.

But for now, the best tool is simple: awareness. If you’re on a long-term medication and feel off - speak up. Your symptoms might not be aging. They might be a reaction. And if they are - you can get your health back.

Can drug-induced lupus turn into regular lupus?

No, drug-induced lupus does not turn into systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). They are two separate conditions. However, in rare cases, someone who develops DIL may later develop SLE independently - but this isn’t because DIL caused it. It means they had an underlying genetic or immune predisposition to autoimmune disease. Stopping the drug and resolving DIL doesn’t increase your risk of SLE.

How long does it take to recover from drug-induced lupus?

Most people start feeling better within 2 to 4 weeks after stopping the triggering medication. Around 80% see major improvement by 4 weeks, and 95% recover fully within 12 weeks. A small number may need short-term steroids to ease lingering symptoms, but long-term treatment is rarely needed.

Can I take the same drug again after recovering?

No. Once you’ve had drug-induced lupus from a specific medication, you should never take it again. Even a small dose can trigger a rapid and severe return of symptoms. Your immune system remembers the trigger. Your doctor will switch you to a safer alternative.

Are over-the-counter drugs linked to drug-induced lupus?

No. There are no known cases of OTC medications like ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or antihistamines causing drug-induced lupus. The drugs linked to DIL are prescription-only, typically used for chronic conditions like high blood pressure, heart rhythm issues, acne, or autoimmune diseases.

Is drug-induced lupus more common in Australia?

No, the incidence of DIL is similar worldwide. However, Australia has an aging population and high use of medications like hydralazine and minocycline, which may lead to more diagnosed cases. Awareness among Australian doctors is growing, and diagnostic delays are improving as more clinicians recognize the pattern.

Johanna Baxter

January 8, 2026OMG I’ve been on minocycline for 3 years and my knees have been killing me-I thought I was just getting old. This post literally saved me. Going to my doc Monday.

Aron Veldhuizen

January 9, 2026Let’s be honest-this is just Big Pharma’s way of shifting blame. You think they care if you get lupus? No. They care if you keep buying pills. The real issue is that we’ve turned medicine into a vending machine: insert symptom, receive drug, pray for results. This isn’t medicine-it’s chemical roulette. And now you want me to believe stopping a drug fixes it? What about the damage done over years of dependency? The system is broken, and this is just a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage.

Chris Kauwe

January 10, 2026Interesting how this gets framed as some American medical revelation, but the truth is, European clinicians have been flagging DIL for decades. We’ve had NAT2 genotyping integrated into prescribing protocols since 2015 in Germany. Meanwhile, American GPs still prescribe hydralazine like it’s aspirin. This isn’t ignorance-it’s institutional negligence. The U.S. healthcare system prioritizes profit over prevention, and DIL is just one more casualty of that paradigm.

Heather Wilson

January 12, 2026While the article presents a compelling narrative, it lacks critical nuance. The claim that DIL "doesn’t stick around" is misleading. A 2021 study in the Journal of Autoimmunity found that 12% of patients experienced residual autoantibody positivity even after 18 months of drug cessation, with 4% developing serologic features consistent with early SLE. Furthermore, the assumption that anti-histone antibodies are pathognomonic is outdated-recent data shows cross-reactivity with other autoimmune triggers, including viral infections. The diagnostic algorithm presented is dangerously oversimplified.

Jenci Spradlin

January 12, 2026Yo I was on minocycline for my acne and my joints started aching like I was 80. I thought I was just stressed. Then I read this and stopped the pill. Two weeks later I could actually bend my knees again. No joke. My doc was like "huh, weird" but I told him to check my anti-histone. Turns out I had DIL. So yeah-ask your doc. Don’t wait.

Meghan Hammack

January 12, 2026This gave me chills. My mom was on hydralazine for 12 years and they kept telling her it was "just arthritis." She finally got diagnosed after collapsing from fatigue. She’s back to gardening now. Thank you for writing this. Please share it with everyone you know on long-term meds.

RAJAT KD

January 14, 2026As a physician in India, I see this often. Patients on minocycline for acne for years, presenting with arthralgia. We rarely test for anti-histone antibodies here due to cost, but we stop the drug empirically. Recovery is almost always complete. Awareness is the key.

Matthew Maxwell

January 16, 2026Anyone who takes prescription medication without understanding its potential autoimmune consequences is complicit in their own decline. This isn’t a medical mystery-it’s a failure of personal responsibility. You don’t just swallow pills and hope for the best. You research. You question. You hold your provider accountable. If you didn’t, you deserve what you get.

Lindsey Wellmann

January 16, 2026😭 I’m so glad I read this. My husband was on infliximab and we thought his fatigue was just "being a dad." Turns out it was DIL. We cried when the symptoms faded after stopping. 🙏❤️

Ashley Kronenwetter

January 17, 2026Thank you for this well-researched and clinically accurate overview. It is refreshing to see a discussion that balances scientific rigor with patient-centered communication. I will be sharing this with my rheumatology colleagues and patients alike.

Kiruthiga Udayakumar

January 18, 2026Why are doctors still prescribing minocycline to people over 50? It’s like giving sugar to diabetics. If you’re over 50 and have joint pain, stop the drug immediately. No excuses. This isn’t a "maybe"-it’s a red flag. I’m not blaming patients-I’m blaming lazy doctors.

Micheal Murdoch

January 20, 2026What’s powerful here isn’t just the medical facts-it’s the reminder that our bodies are still speaking to us, even when medicine stops listening. We’ve been trained to ignore fatigue, to normalize pain, to accept "aging" as inevitable. But your body isn’t broken. It’s signaling. And sometimes, the fix isn’t another pill-it’s the courage to say, "I’m stopping this." That’s not weakness. That’s wisdom.

tali murah

January 20, 2026Oh please. "Drug-induced lupus" is just a fancy term for "you took something and your immune system got annoyed." If your body reacts badly to a drug, you shouldn’t have taken it. End of story. This isn’t a medical breakthrough-it’s a failure of patient education. If you don’t read the damn side effects, you’re not a victim. You’re a statistic.

Jeffrey Hu

January 21, 2026Actually, the 95% recovery rate is misleading. That’s based on self-reported surveys, not blinded trials. The real data from the Mayo Clinic registry shows only 72% achieve full symptom resolution within 12 weeks. Also, anti-histone antibodies can be positive in drug-induced hepatitis and even in some infections. This article reads like a pharma-sponsored blog post.

Angela Stanton

January 23, 2026So let me get this straight… you’re telling me that after years of being told I have lupus, I might just have a reaction to a drug I was on for acne? 🤯 I’ve been on Plaquenil for 5 years. I’m going to lose my mind if this is true. Also-emoji time: 🧪💊😭