Blood Cancer Trial Phase Calculator

How Clinical Trial Phases Work

This calculator shows which phase a clinical trial belongs to based on participant count. Understanding these phases helps patients see where new treatments are in development.

Trial Phase Result

Enter a participant count to see the corresponding trial phase

When it comes to beating blood cancers like leukemia, lymphoma, or multiple myeloma, the fastest path to new, life‑saving treatments runs through clinical trials for blood cancer. These studies aren’t just paperwork - they’re the engine that turns lab discoveries into real‑world cures.

Key Takeaways

- Clinical trials are the primary way new blood‑cancer therapies move from theory to practice.

- Each trial phase (I, II, III) has a distinct purpose and safety focus.

- Patient participation speeds up discovery and improves survival odds.

- Regulatory bodies like the FDA ensure trials meet strict ethical standards.

- Finding a trial is easier than ever thanks to searchable registries such as ClinicalTrials.gov.

What Exactly Is a Clinical Trial?

Clinical trials are research studies that evaluate how well new medical approaches work in people. They follow a predefined protocol, track outcomes, and compare results against existing treatments or placebos. For blood cancers, trials often test novel drugs, cell therapies, or combination regimens.

These studies answer three big questions: Is the treatment safe? Does it work better than what we have now? And can it improve quality of life?

Why Blood Cancer Needs Dedicated Trials

Blood cancer refers to malignancies that start in the bone marrow or the blood‑forming system-primarily leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. Unlike solid tumors, blood cancers spread through the bloodstream, making them uniquely responsive to systemic therapies like targeted drugs or immunotherapies.

Because the disease mechanisms differ so much, a drug that works for breast cancer might do nothing for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Dedicated trials ensure that each therapy is tested against the specific biology of blood cancers.

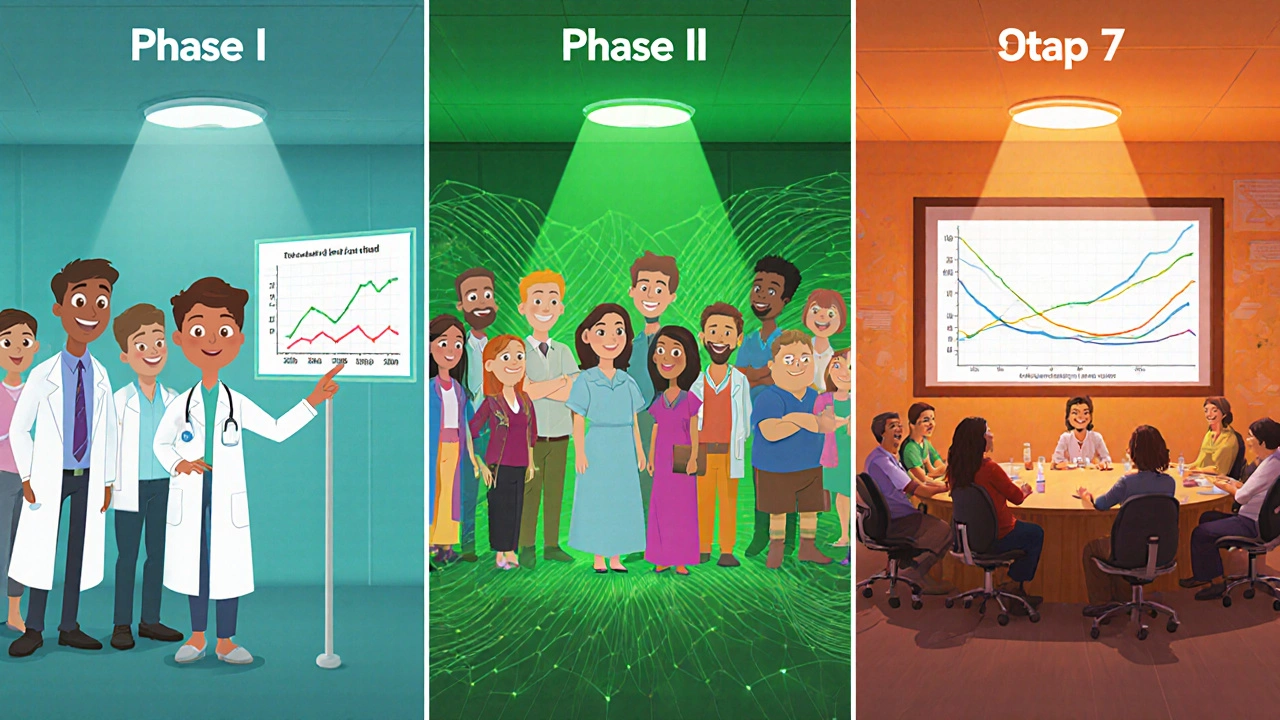

How Trials Are Structured: Phases Explained

| Phase | Primary Goal | Typical Participants | Key Outcomes Measured |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Safety and dosage | 20‑80 healthy volunteers or patients with advanced disease | Adverse events, maximum tolerated dose |

| Phase II | Efficacy and further safety | 100‑300 patients with specific blood‑cancer subtype | Response rate, progression‑free survival |

| Phase III | Confirm benefit vs standard of care | 300‑3,000 patients across multiple centers | Overall survival, quality‑of‑life, long‑term safety |

Each phase builds on the previous one, creating a safety net that protects participants while gathering robust data.

Breakthroughs Born from Blood‑Cancer Trials

Some of the most talked‑about advances started in a trial setting. CAR‑T cell therapy, for example, re‑programs a patient’s own T cells to hunt down cancer cells. The first successful CAR‑T trials for acute lymphoblastic leukemia reported remission rates above 80% in heavily pre‑treated patients.

Another game‑changer is the class of drugs called BTK inhibitors, which target a protein critical for B‑cell malignancies. Trials demonstrated dramatic reductions in disease progression for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, leading to FDA approval in 2013.

How Patients Can Join a Trial

ClinicalTrials.gov is a public database that lists thousands of ongoing oncology studies worldwide. By entering keywords like "acute myeloid leukemia" and filtering by location, patients can find trials that match their diagnosis, age, and treatment history.

Once a potential trial is identified, the next steps usually involve:

- Talking to the treating hematologist about suitability.

- Reviewing the informed consent form, which explains risks, benefits, and what to expect.

- Undergoing baseline tests (blood work, imaging) to confirm eligibility.

- Signing the consent and starting the study protocol.

Doctors often work with trial coordinators to handle paperwork and schedule visits, making the process smoother for patients.

Addressing Common Concerns

Many potential participants worry about safety. It’s true that early‑phase trials test new compounds, but they follow strict monitoring guidelines. Serious adverse events are reported to Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and the FDA, and the study can be halted if risks become unacceptable.

Another myth is that trial patients receive “experimental” care that’s inferior to standard therapy. In reality, most trials compare a new treatment **against** the best available standard, so participants often receive cutting‑edge care plus additional monitoring.

The Bigger Picture: How Trials Accelerate Research

Every enrolled patient contributes data that help researchers understand which therapies work, for whom, and why. Large Phase III studies provide the statistical power needed for regulatory approval, while smaller early‑phase trials identify promising signals quickly.

When trials succeed, the results are published in peer‑reviewed journals and incorporated into clinical guidelines such as NCCN or ESMO. This cascade turns a single patient’s experience into a benefit for thousands.

Frequently Asked Questions

What types of blood cancer are most often studied in trials?

Leukemia (especially acute myeloid and lymphoblastic), lymphoma (Hodgkin and non‑Hodgkin), and multiple myeloma receive the bulk of research focus because they have distinct molecular drivers and unmet treatment needs.

How long does a typical blood‑cancer trial last?

Phase I studies may run 6‑12 months, while Phase III trials often span 2‑5 years, depending on enrollment speed and endpoint maturity.

Are there financial costs for patients?

Most trial‑related procedures and the investigational drug are provided at no cost. However, routine care not covered by the study (like standard imaging) may be billed to insurance or the patient.

Can I join a trial if I’m already on treatment?

Eligibility criteria vary. Some trials accept patients who have completed prior therapy, while others target those newly diagnosed or refractory to standard regimens. Your oncologist can match your status to appropriate studies.

What role does the FDA play in blood‑cancer trials?

The FDA reviews trial designs, monitors safety reports, and ultimately decides whether a new therapy can be marketed based on the trial’s evidence of efficacy and safety.

Bill Bolmeier

October 15, 2025If you’re on the fence about signing up for a trial, remember it could be the fastest route to a cutting‑edge therapy. Every extra patient helps speed the data that could save someone else later.

Darius Reed

October 17, 2025Yo, the whole thing ain’t some sci‑fi movie where you get zapped into a lab; it’s real people, real hopes, and real data. You’ll get regular check‑ups, some extra pills, and a stack of paperwork that’ll make you feel like a secret agent. The best part? You’re literally part of a story that might write the next cure. Just make sure you read the consent form – it’s a scroll, not a napkin.

Karen Richardson

October 19, 2025Clinical‑trial phases follow a strict hierarchy: Phase I focuses on safety and dosage, enrolling roughly 20‑80 participants to determine the maximum tolerated dose. Phase II expands to 100‑300 patients, assessing efficacy while continuing safety monitoring and measuring response rates. Phase III involves several hundred to a few thousand subjects across multiple sites to confirm therapeutic benefit versus the current standard of care, often using overall survival as the primary endpoint. Each phase must meet predefined statistical thresholds before advancing, ensuring that only promising agents reach the market.

AnGeL Zamorano Orozco

October 21, 2025Look, the textbook breakdown is neat, but the reality is a battlefield of hope and bureaucracy where every extra data point feels like a tiny victory against an invisible enemy. Researchers scramble like mad scientists, participants brave the unknown, and regulators sit on their thrones demanding flawless protocols. If you think Phase I is just “safety”, think again – it’s a crucible where lives are weighed against the promise of a miracle. Phase II? That’s the proving ground where optimism meets hard‑core statistics. By the time you hit Phase III, you’re watching a massive chess game, each move watched by investors, families, and the media. And all the while, the clock ticks, and every delay could mean another patient missing out.

Cynthia Petersen

October 23, 2025Sure, signing up for a trial sounds like signing up for a reality TV show, but the stakes are way higher – your health, not just ratings. The good news? You get access to therapies that haven’t hit the shelves yet, plus the occasional perk like travel reimbursements. Think of it as a chance to turn the tables on the disease while the scientists get their data. If nothing else, you’ll have a compelling story to tell at the next family dinner.

John Petter

October 25, 2025Trials give you a new drug and close monitoring.

Tina Johnson

October 27, 2025The statement, while factually correct, omits the critical nuance that trial participation also entails rigorous eligibility screening, potential side‑effects, and a commitment to follow‑up visits, all of which must be weighed against the prospective benefits. Therefore, prospective participants should engage in thorough discussions with their oncology team to fully understand the obligations and risks involved.

Sharon Cohen

October 29, 2025Honestly, the hype around clinical trials often overshadows the fact that many studies never reach a conclusive endpoint, leaving participants with no tangible advances.

Rebecca Mikell

October 31, 2025While it’s true some trials stall, each one adds a piece to the puzzle, and the collective data drives future breakthroughs that eventually improve standard‑of‑care protocols for patients worldwide.

Alyssa Griffiths

November 2, 2025Wow!!! Did you know that the “clinical trials” narrative is often pushed by big pharma??? They claim it’s all about patient safety, yet the data they release is carefully curated… Beware of the hidden agendas!!!

dany prayogo

November 4, 2025It’s amusing how the medical community loves to parade “clinical trials” as the golden ticket, yet they conveniently forget that the majority of these studies are sponsored by corporations whose bottom line eclipses altruism. First, the recruitment ads paint a rosy picture, promising cutting‑edge treatment while glossing over the mountain of paperwork and invasive procedures that participants must endure. Second, the consent forms are legally dense tomes that most patients skim, never truly grasping the scope of potential side effects. Third, the eligibility criteria are so restrictive that only a narrow subset of the population qualifies, rendering the results less applicable to the average patient. Fourth, interim analyses often get cherry‑picked to showcase favorable trends, while unfavorable data is buried in supplemental files. Fifth, the FDA’s “fast‑track” designations can accelerate approval, but they also compress the safety evaluation timeline, occasionally leading to post‑market withdrawals. Sixth, the media hype surrounding a breakthrough trial can inflate expectations, only to leave patients disillusioned when the therapy fails to deliver in the real world. Seventh, the financial incentives for investigators-who may receive per‑patient bonuses-introduce subtle pressures to enroll as many participants as possible, sometimes at the expense of rigorous screening. Eighth, the massive cost of these trials is ultimately subsidized by taxpayers, who are rarely informed about how their money is allocated. Ninth, the “patient advocacy” groups that champion trial enrollment are often funded by the same pharmaceutical entities whose drugs they promote, creating a conflict of interest that goes undisclosed. Tenth, the statistical endpoints, such as progression‑free survival, can be manipulated through crossover designs, muddying the interpretation of true clinical benefit. Eleventh, the sheer volume of ongoing trials fragments enrollment, leading to underpowered studies that can’t conclusively answer the research question. Twelfth, the post‑trial follow‑up is frequently inadequate, leaving long‑term safety data scarce. Thirteenth, the narratives crafted by press releases tend to overstate efficacy, using language that sounds optimistic but is scientifically vague. Fourteenth, the regulatory approval process, while rigorous, is not immune to political and economic lobbying that can sway decision‑making. Fifteenth, the patients who do participate often become the unsung heroes, their contributions acknowledged only in the fine print of academic papers. Finally, despite these myriad flaws, the system does occasionally produce genuine breakthroughs, reminding us that the process, though imperfect, still holds the potential to transform lives if we remain vigilant and demand transparency at every step.

Wilda Prima Putri

November 6, 2025Wow, that was a marathon read – love the passion, and yeah, the system isn’t perfect. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, just remember that every data point still pushes the needle forward, even if it’s a slow crawl.

Sharif Ahmed

November 8, 2025The discourse surrounding hematologic oncology trials often suffers from a lack of literary flourish, yet the gravity of the subject demands a narrative as sophisticated as the molecular pathways we probe.

Arjun Santhosh

November 10, 2025i think the key point is that patients should weigh the pros and cons, not just jump in because “new is better”. sometimes the old standard works fine, and trial side effects can be a real headache.

Stephanie Jones

November 11, 2025In the grand tapestry of medical progress, each trial is but a single thread, subtle yet essential, weaving together hope and evidence in a quiet, relentless march toward cure.

Chelsea Kerr

November 13, 2025🔬✨ Clinical trials are the crucible where curiosity meets compassion; they transform abstract hypotheses into tangible hope. By enrolling, you become a co‑author of future medical textbooks, and the data you provide may light the way for countless others. 🌟💉

Tom Becker

November 15, 2025yeah, “new drug” vibes sound cool but remember some of those “breakthroughs” were just clever marketing, and the side‑effects often get swept under the rug in the hype train.