TNF inhibitors are not magic bullets, but for millions of people with autoimmune diseases, they’ve been the difference between living in pain and living normally. These drugs don’t just mask symptoms-they stop the body’s own immune system from tearing itself apart. If you’ve been told your rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or Crohn’s disease isn’t responding to pills like methotrexate, your doctor might suggest a TNF inhibitor. But how do they actually work? And why do they help some people so much while doing nothing-or even causing problems-for others?

What TNF Alpha Does in Your Body

Tumor necrosis factor alpha, or TNFα, sounds scary because it has “tumor” in the name. But it’s not causing cancer. It’s a signaling protein your body makes naturally. Think of it as an alarm bell. When your immune system detects an infection-say, a cut getting infected or a virus invading-TNFα gets released. It tells nearby cells to wake up, recruit more immune fighters, and start inflammation. That’s supposed to be helpful. Inflammation is how your body isolates and kills invaders. But in autoimmune diseases, the alarm bell rings when there’s no real threat. Your immune system mistakes your own joints, skin, or gut lining for an enemy. TNFα floods the area, pulling in white blood cells, triggering more chemicals like IL-1 and IL-6, and causing swelling, pain, and tissue damage. In rheumatoid arthritis, it erodes cartilage. In Crohn’s, it creates ulcers. In psoriasis, it forces skin cells to grow too fast. TNFα sits at the top of this chain. Block it, and you shut down a big part of the damage.The Five TNF Inhibitors and How They’re Different

There are five FDA-approved TNF inhibitors on the market, and they’re not all the same. They fall into two groups based on how they’re made. The first is etanercept (Enbrel). It’s not an antibody. It’s a fusion protein-basically, it’s a piece of the TNF receptor (the part that normally grabs TNFα) glued to a human antibody tail. Think of it like a sponge that soaks up free-floating TNFα before it can reach your cells. It doesn’t bind well to TNF stuck on cell surfaces, so its effect is more limited. The other four-infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), golimumab (Simponi), and certolizumab pegol (Cimzia)-are monoclonal antibodies. These are lab-made versions of immune proteins designed to lock onto TNFα like a key in a lock. Infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab are full antibodies that can bind both free TNF and TNF stuck to cell membranes. That means they can do more than just block: they can flag cells for destruction by your immune system (a process called antibody-dependent cytotoxicity). Certolizumab is different. It’s a fragment of an antibody, stripped of its tail, and attached to polyethylene glycol (PEG). That makes it smaller and lets it spread further in tissues, but it can’t trigger immune cell destruction. It only blocks soluble TNF. These differences affect how they’re given. Etanercept and adalimumab are injected under the skin every week or two. Infliximab has to be given through an IV drip, usually every 4 to 8 weeks. Golimumab is monthly. Certolizumab is every 2 to 4 weeks. Some people prefer injections at home. Others don’t mind going to a clinic for infusions.How TNF Inhibitors Actually Stop the Damage

It’s not just about blocking TNFα. Once you stop TNF from binding to its receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2), a whole cascade of inflammation shuts down. Less IL-8 means fewer white blood cells rushing to the site. Less E-selectin means immune cells can’t stick to blood vessel walls to sneak into tissues. Less ICAM-1 means less cell-to-cell signaling that fuels chronic inflammation. But here’s where it gets complicated. TNF inhibitors don’t just sit there and block. They can also trigger cell death. Monoclonal antibodies like adalimumab can signal immune cells to kill cells that are producing too much TNF-like overactive immune cells in your joints. They can also cause apoptosis, or programmed cell death, in some of the very cells driving the disease. Studies show that after starting a TNF inhibitor, levels of other inflammatory markers like CRP and ESR drop significantly within weeks. In rheumatoid arthritis patients, X-rays often show less joint damage after a year compared to those on older drugs like methotrexate alone. That’s huge. For decades, doctors could only slow joint destruction. Now, with TNF inhibitors, many patients stop it entirely.

Who Benefits-and Who Doesn’t

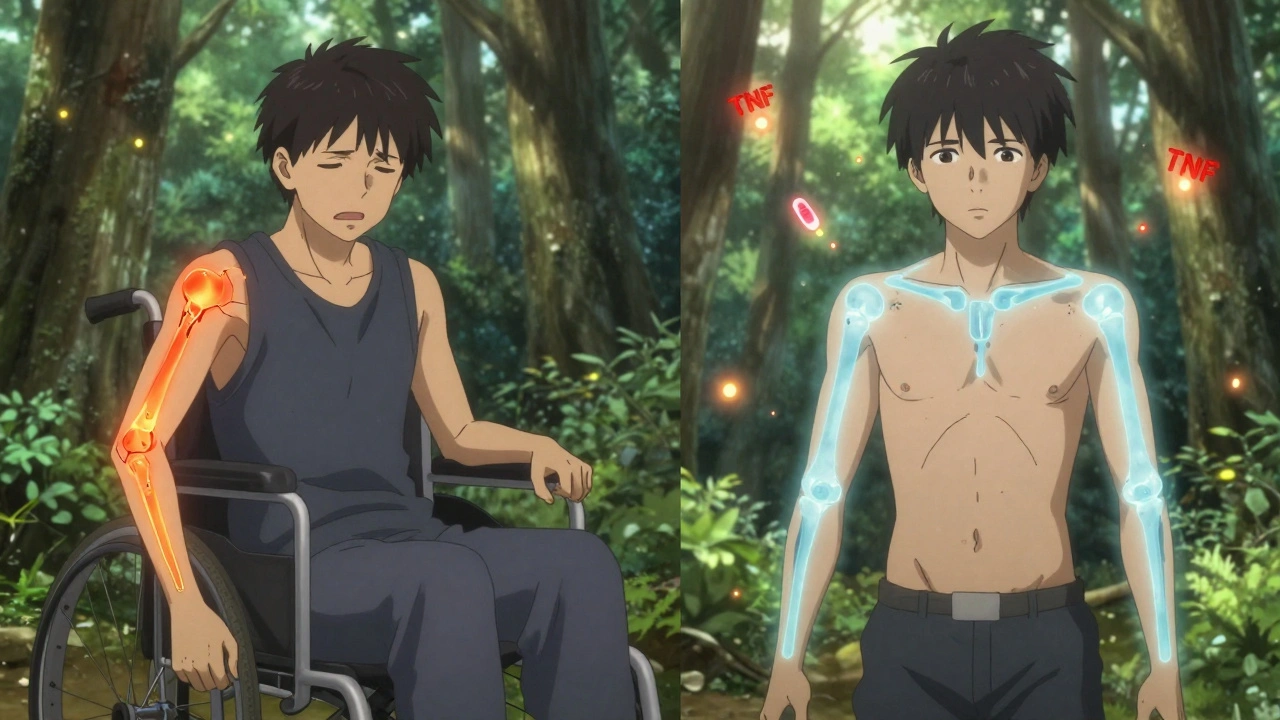

About 50 to 60% of people with rheumatoid arthritis see major improvement on TNF inhibitors. That’s a big jump from the 20 to 30% who respond to traditional DMARDs. For some, it’s life-changing. One patient I spoke with went from needing a cane to hiking 5 miles a week after six months on adalimumab. In psoriasis, up to 75% of patients clear 75% or more of their skin lesions. But not everyone responds. About 30 to 40% of people experience what’s called secondary failure. The drug works at first-then, after months or even years, it stops. Why? Often, the body starts making anti-drug antibodies. Your immune system sees the TNF inhibitor as a foreign invader and attacks it. That’s more common with monoclonal antibodies than with etanercept. When this happens, the drug gets cleared from your blood before it can work. Some people just don’t respond at all from the start. That’s called primary non-response. It’s not your fault. It’s biology. Researchers are still trying to figure out why. Genetic differences, the specific type of autoimmune disease, or even gut bacteria may play a role.The Hidden Risks: Infections and Paradoxical Reactions

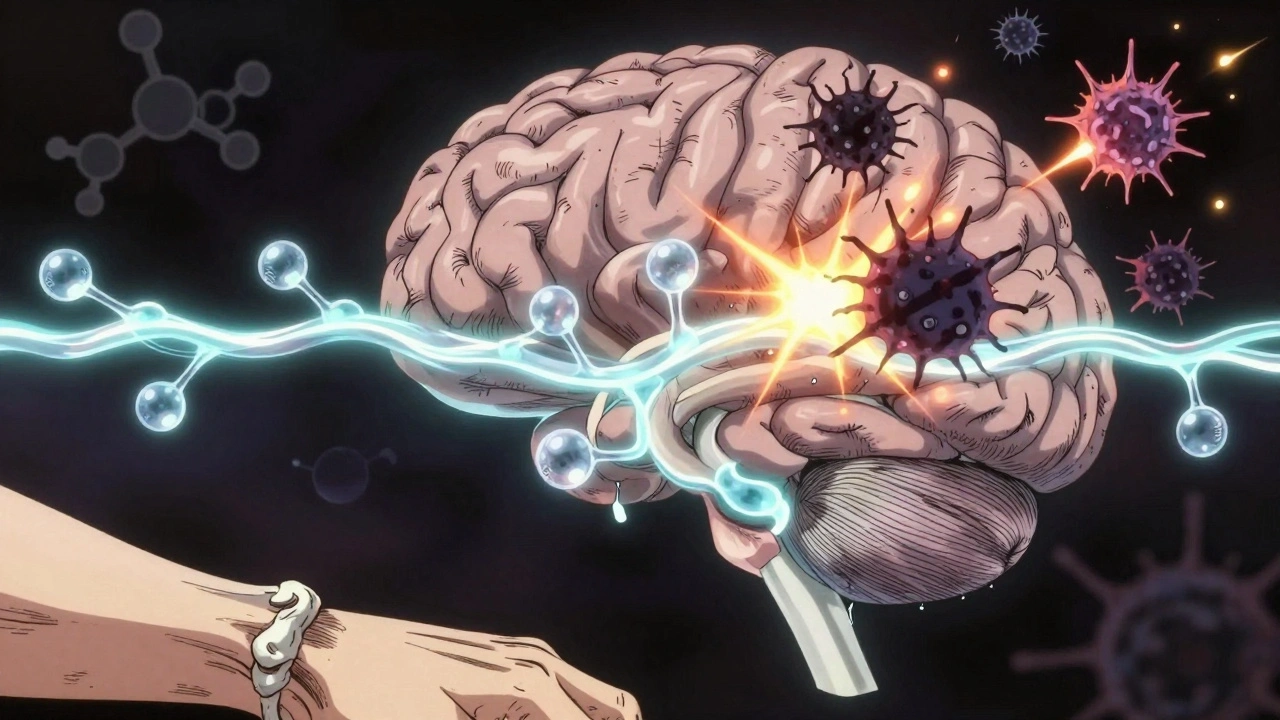

Blocking TNFα is like turning off a fire alarm. It stops the noise, but it also means you won’t hear if there’s a real fire. That’s why people on TNF inhibitors have a 2 to 5 times higher risk of serious infections. Tuberculosis is a big one. Before starting treatment, you get a skin test or blood test for latent TB. If it’s positive, you take antibiotics first. Fungal infections like histoplasmosis are also more common, especially in certain regions. There’s another strange side effect: paradoxical inflammation. Some patients develop psoriasis, lupus-like symptoms, or even multiple sclerosis-like neurological problems after starting a TNF inhibitor. Why? Because TNFα isn’t just bad. It also helps regulate the immune system. In the brain, TNF inhibitors can’t cross the blood-brain barrier. So while they calm inflammation in your joints, they might accidentally trigger inflammation in your nervous system by disrupting immune balance. Research suggests blocking TNF can cause autoreactive T cells to survive longer and migrate into the CNS, triggering damage. A 2020 study in JAMA Neurology found that patients on TNF inhibitors had more than double the risk of inflammatory central nervous system events compared to those not on the drugs. It’s rare, but it’s real. That’s why doctors monitor for new neurological symptoms-tingling, vision changes, weakness-very closely.

What Comes After TNF Inhibitors?

TNF inhibitors revolutionized autoimmune care in the 2000s. But they’re not the end of the road. Newer biologics target other parts of the immune system. IL-17 inhibitors like secukinumab work great for psoriasis. IL-23 blockers like guselkumab are even more effective for some skin conditions. JAK inhibitors like tofacitinib are pills that block signals inside immune cells, not outside. Still, TNF inhibitors remain first-line biologics for many. They’re the most studied. Their long-term safety profile is better understood than newer drugs. And for many, they’re still the most effective. Biosimilars-copies of the original drugs-are now widely available. Amjevita, a biosimilar to Humira, costs significantly less. That’s opened access for many who couldn’t afford the brand-name version. Insurance often pushes patients to try biosimilars first.What to Expect When You Start

Starting a TNF inhibitor isn’t a one-time fix. It’s a commitment. You’ll need regular blood tests to check liver function and blood counts. You’ll need to report any fever, cough, or unusual fatigue right away. Injections can cause redness or itching at the site-about 1 in 3 people deal with this. Some find it frustrating. Others get used to it. Manufacturers offer support programs. AbbVie’s Humira Complete gives you 24/7 nursing help, injection training, and co-pay assistance. Janssen’s Inflectra Connect does the same for Remicade. These aren’t just perks-they’re critical for sticking with treatment. It takes 3 to 6 months to see the full effect. Don’t give up if you don’t feel better after a month. Some patients need to switch drugs. But for many, the trade-off is worth it. Pain fades. Mobility returns. Life gets back.How long does it take for TNF inhibitors to work?

Most people start noticing less pain and swelling within 4 to 6 weeks, but it can take up to 3 to 6 months to see the full benefit. Patience is key-this isn’t a painkiller that works in an hour. It’s rebuilding your immune balance over time.

Can I stop taking TNF inhibitors if I feel better?

Usually not. Stopping the drug often leads to a flare-up of symptoms within weeks or months. Some patients in remission may try to taper under close supervision, but most need to stay on it long-term to keep the disease controlled. It’s not a cure-it’s ongoing management.

Do TNF inhibitors cause weight gain?

Not directly. But some people gain weight because they’re able to move more once their pain decreases. Others may gain due to steroid use alongside biologics. Weight gain isn’t a known side effect of TNF inhibitors themselves.

Are TNF inhibitors safe during pregnancy?

Some are. Adalimumab and certolizumab pegol cross the placenta less than others, so they’re often preferred during pregnancy. Etanercept is also considered relatively safe. Infliximab and golimumab are used when needed, but doctors prefer to avoid them in the third trimester. Always discuss this with your rheumatologist before trying to conceive.

Why do some TNF inhibitors require IV infusions while others are injections?

It’s about size and stability. Infliximab is a large antibody molecule that breaks down too quickly if taken orally or under the skin. It must be given directly into the bloodstream. Smaller molecules like adalimumab or etanercept are stable enough to be injected under the skin and absorbed slowly over days. Certolizumab’s PEG coating helps it last longer in the body, allowing less frequent dosing.

What happens if a TNF inhibitor stops working?

Your doctor will likely switch you to another biologic-maybe one that targets IL-17, IL-23, or JAK pathways. Sometimes, adding a low-dose methotrexate can help your body stop making antibodies against the drug. Testing for anti-drug antibodies can guide the decision. Never stop or change your dose without medical advice.

Aman deep

December 12, 2025man i read this whole thing and i just wanna hug someone who gets it. i’ve been on humira for 4 years and yeah, the injections suck, but the fact that i can now pick up my kid without crying? worth every needle prick. also, tb screening is no joke-got scared when mine came back latent but the meds fixed it before anything blew up. thanks for writing this.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

December 14, 2025it’s wild how something that sounds like a sci-fi weapon-blocking your own body’s alarm system-is what lets people walk again. we think of medicine as fixing broken parts, but this is more like turning down a volume knob that got stuck on 11. and yet… we’re still learning how loud the silence gets after you turn it off.

Eddie Bennett

December 14, 2025my uncle was on infliximab and got histoplasmosis in kentucky. no one warned him about fungi being a thing. doc just said ‘watch for fever.’ like that’s enough? also, the whole ‘paradoxical psoriasis’ thing is creepy. you fix one thing and suddenly your skin turns into a lava lamp. science is cool until it turns on you.

Sylvia Frenzel

December 15, 2025why do we let big pharma charge $20k a year for drugs that were funded by taxpayer research? this isn’t innovation, it’s exploitation. and don’t even get me started on biosimilars being pushed like they’re inferior. they’re the same damn thing.

Paul Dixon

December 16, 2025my sister switched from humira to amjevita and saved like $15k a year. same results, same side effects, just cheaper. insurance made her switch and honestly? she’s happier now. why are we still acting like brand names are magic?

Vivian Amadi

December 17, 2025you people act like this is some miracle cure. it’s not. it’s just a bandaid on a bullet wound. and you’re all just happy to be alive while ignoring the fact that you’re now a walking infection risk. also, ‘patience’? i waited 6 months and got zero results. waste of time and money.

Ariel Nichole

December 18, 2025really appreciate how you broke down the differences between the drugs. i had no idea certolizumab couldn’t trigger cell death. that’s actually super helpful. my doc just said ‘here’s your script’ and i didn’t ask questions. now i feel way more informed.

matthew dendle

December 19, 2025so let me get this straight… you inject a protein that stops your body from attacking itself… but then your body attacks the protein? lol. so we’re just playing whackamole with our immune system now? and you call this medicine? sounds like a bad video game.

Monica Evan

December 19, 2025as someone who’s been on etanercept since 2018, i can tell you the real win isn’t just less pain-it’s being able to sleep through the night. no more 3am joint screams. also, typo: ‘TNFα’ not ‘TNFa’-little alpha matters. and yes, the PEG in certolizumab is genius. lets it sneak into joints better. just sayin’.

Taylor Dressler

December 19, 2025the mechanism of action here is one of the most elegant examples of targeted immunotherapy. blocking TNFα doesn’t suppress the entire immune system-it selectively dampens a pathological cascade. this is precision medicine at its best. and yes, the difference between fusion proteins and monoclonal antibodies matters clinically. etanercept’s inability to bind membrane-bound TNF explains its lower efficacy in some Crohn’s cases.

Aidan Stacey

December 21, 2025i used to be bedridden. now i hike. i paint. i dance with my wife. this isn’t just a drug-it’s a second chance. and yeah, the needle scares me every time. but i look at my daughter’s face and i don’t care. if you’re scared to try this, i get it. but don’t let fear steal your life. you’ve got more strength than you know.

Mia Kingsley

December 22, 2025you’re all acting like this is the holy grail. what about the 40% who get zero results? what about the ones who get MS-like symptoms? why is no one talking about how many people end up worse? this is just the latest pharmaceutical fad. wait till the next ‘miracle’ drug comes along and everyone forgets this one nearly killed them.

Katherine Liu-Bevan

December 23, 2025the data on pregnancy safety is solid, but most OB-GYNs still panic when they see ‘biologic’ on a chart. i was on adalimumab during both pregnancies-no complications. my kids are 5 and 7, healthy as horses. if you’re considering pregnancy, talk to a rheumatologist who actually understands this, not the one who thinks ‘biologic’ means ‘dangerous.’

Courtney Blake

December 24, 2025you’re all so grateful. like ‘oh i can walk again!’ wow. big deal. meanwhile, i’m paying $500 a month out of pocket because my insurance hates me. and you think this is progress? this is capitalism with a stethoscope. you’re not cured-you’re just a paying customer.

Lisa Stringfellow

December 24, 2025why are we still using 20-year-old drugs? why not just admit TNF inhibitors are outdated? everyone’s just clinging to them because they’re ‘well-studied.’ that’s not science, that’s laziness. we need new targets. and stop pretending biosimilars are ‘just as good.’ they’re not.