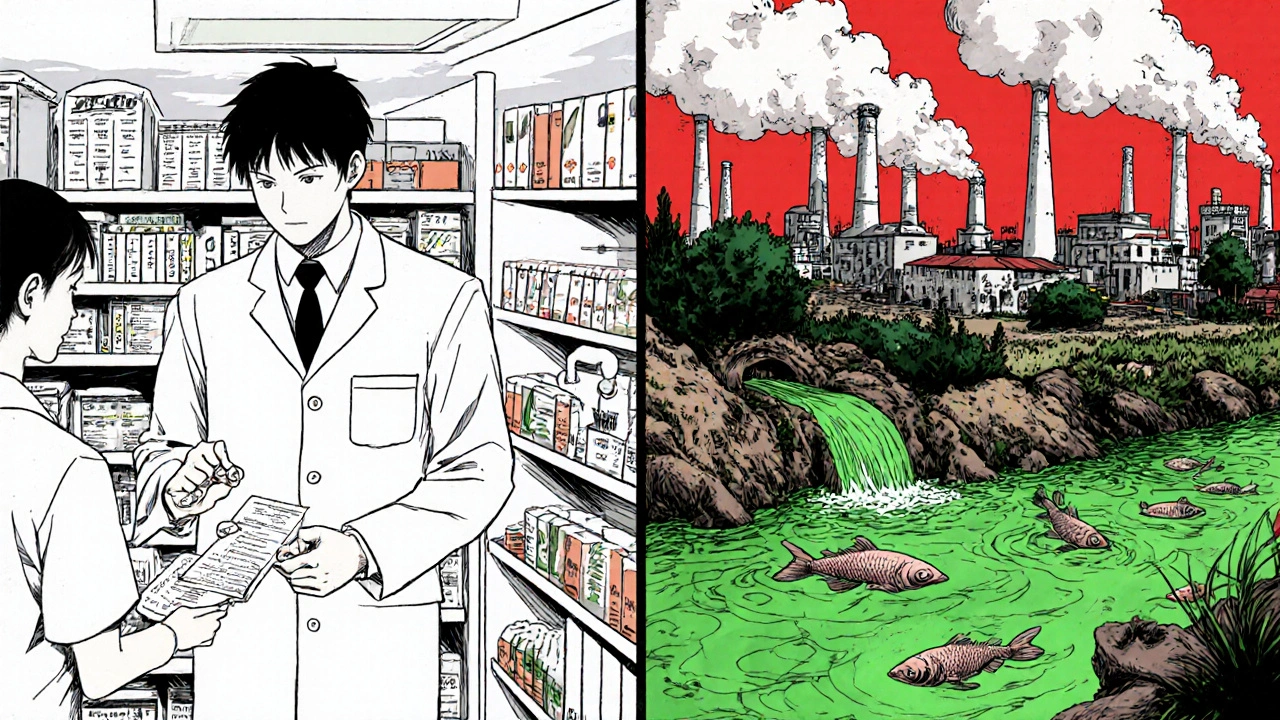

Allopurinol is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs for gout and kidney stones. It works by lowering uric acid in the blood, preventing painful flare-ups. But behind every pill is a complex, resource-heavy process that leaves a hidden environmental footprint. Most people don’t think about where their medication comes from - but the production of allopurinol involves toxic chemicals, massive water use, and chemical waste that ends up in rivers and soil. This isn’t just a problem in distant factories. It’s part of a global pattern where life-saving drugs come at a cost to the planet.

How Allopurinol Is Made

Allopurinol is a synthetic compound. It doesn’t come from plants or animals - it’s built in chemical reactors using raw materials like cyanide, ammonia, and chlorinated hydrocarbons. The synthesis starts with cyanoacetamide, which reacts with urea under high heat and pressure. This step alone produces hydrogen chloride gas as a byproduct. That gas has to be captured and neutralized, or it escapes into the air. In poorly regulated facilities, it doesn’t always get caught.

After the initial reaction, the mixture goes through multiple purification stages. Solvents like methanol and acetone are used to isolate the pure allopurinol crystals. These solvents aren’t reusable in full. About 30% of the solvent used in each batch ends up as wastewater. That wastewater contains traces of unreacted chemicals, heavy metal catalysts, and organic residues. In countries with weak environmental laws, this wastewater is dumped directly into rivers. A 2023 study in India found allopurinol residues in surface water near three major pharmaceutical hubs, with concentrations high enough to affect aquatic life.

Water Use and Energy Demands

Producing one kilogram of allopurinol requires between 8,000 and 12,000 liters of water. Most of that isn’t for the drug itself - it’s for cooling reactors, cleaning equipment, and washing out impurities. In regions like Gujarat or Henan, where water is already scarce, this puts pressure on local communities. Farmers downstream from these factories report lower crop yields and contaminated wells.

Energy use is just as heavy. The synthesis needs constant high temperatures, and purification requires vacuum distillation and freeze-drying. A single production line running 24/7 can consume as much electricity as a small town. In China, where about 60% of the world’s allopurinol is made, most of that power still comes from coal. That means every pill you take carries a carbon footprint of roughly 0.2 kg of CO₂ equivalent. Multiply that by the 200 million prescriptions filled globally each year, and you’re looking at over 40,000 metric tons of CO₂ - equivalent to driving 100 million kilometers in a gasoline car.

Chemical Waste and Pollution

The biggest issue isn’t just the waste water - it’s the sludge. After solvent extraction, the leftover sludge contains heavy metals like chromium and nickel, used as catalysts in earlier steps. It also holds unreacted cyanide compounds, which are extremely toxic. In proper facilities, this sludge is incinerated in high-temperature furnaces with scrubbers. But in smaller or illegal operations, it’s simply buried or dumped. A 2022 investigation by the Global Alliance on Health and Pollution found allopurinol production waste in 17 open landfill sites across Southeast Asia and South Asia. Soil samples from those sites showed levels of cyanide 80 times above safe limits.

Even when waste is treated, the process isn’t perfect. Advanced oxidation systems can break down organic pollutants, but they don’t remove all traces of allopurinol. The drug itself is persistent - it doesn’t break down easily in water. Studies show it can survive wastewater treatment plants and end up in drinking water sources. In 2024, researchers in Germany detected allopurinol in tap water at levels of 0.02 micrograms per liter. That’s low, but it’s still there - and we don’t yet know the long-term effects of chronic low-dose exposure.

Who Bears the Cost?

The environmental damage from allopurinol production doesn’t show up on your pharmacy receipt. It shows up in the fish dying in Indian rivers, in the children in Bangladesh with elevated lead levels, in the farmers who can’t grow rice anymore. The people who pay the price are rarely the ones taking the pills. Most allopurinol users live in North America, Europe, or Australia - places with strict regulations and clean water. The factories making the drug? They’re mostly in India, China, and Pakistan, where environmental oversight is weaker and enforcement is inconsistent.

Pharmaceutical companies argue they follow international standards. But those standards vary wildly. The European Union requires full waste tracking and treatment. The U.S. has loose rules for exported drugs. And in many developing countries, there’s no system at all. A 2023 report from the World Health Organization found that only 28% of pharmaceutical manufacturers in low-income countries had proper wastewater treatment. That means more than seven in ten allopurinol pills may have been made under conditions that harmed local ecosystems.

What’s Being Done?

Some companies are changing. A few European manufacturers have switched to closed-loop solvent systems that recycle 95% of their chemicals. One German firm reduced water use by 70% by using membrane filtration instead of traditional washing. Another in Switzerland now uses biocatalysts instead of heavy metal catalysts, cutting toxic sludge by 90%.

Green chemistry is slowly making its way into pharma. The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry - developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency - are being adopted by forward-thinking firms. These include using safer solvents, designing for degradation, and minimizing energy use. But adoption is patchy. Most generic drug makers operate on razor-thin margins. They can’t afford the upfront cost of cleaner tech. So they stick with the cheap, dirty methods.

There’s also pressure from regulators. The European Medicines Agency now requires environmental risk assessments for new drugs. Allopurinol was reviewed in 2024, and manufacturers were asked to submit data on their waste streams. Some responded with detailed reports. Others didn’t. The result? A few brands now carry a ‘Low Environmental Impact’ label - but it’s voluntary. You won’t find it on the bottle unless you look for it.

What You Can Do

You don’t have to stop taking allopurinol. It’s a vital medication for many. But you can ask questions. When you refill your prescription, ask your pharmacist: “Is this made by a manufacturer with certified environmental practices?” Some pharmacies now source from greener suppliers. If you’re on a long-term prescription, you might have options.

Support organizations pushing for transparency in drug manufacturing. Groups like Pharmacy Without Borders and the Clean Medicines Initiative are lobbying for mandatory environmental reporting from all pharmaceutical companies. You can sign petitions, write to your health minister, or join campaigns calling for a global standard for green pharma.

And if you’re able, choose generic brands that disclose their manufacturing practices. Some companies, like Teva and Mylan, have published sustainability reports. Others don’t. Knowing where your medicine comes from isn’t just about safety - it’s about responsibility.

The Bigger Picture

Allopurinol is just one drug. But it’s a mirror. It shows how medicine, for all its benefits, is still tied to an industrial system that treats the planet as an open sewer. We’ve made huge progress in treating disease. Now we need to make the same progress in protecting the environment that gives us clean air, water, and soil - the very things we need to stay healthy.

The next generation won’t care how well we treated gout. They’ll ask: Did you fix the pollution while you were at it?

Is allopurinol harmful to the environment?

Yes, the production of allopurinol generates toxic chemical waste, uses large amounts of water and energy, and releases pollutants into air and water. Residues of the drug itself have been found in rivers and even tap water in some regions. While the drug is safe for human use, its manufacturing process has significant environmental costs.

Where is allopurinol mainly produced?

About 60% of the world’s allopurinol is manufactured in China, with major production also in India and Pakistan. These countries have large generic drug industries, but environmental regulations are often less strict than in the U.S. or EU. Waste from these factories has been linked to water contamination in nearby communities.

Can allopurinol be made in an eco-friendly way?

Yes. Some manufacturers are adopting green chemistry techniques: recycling solvents, using biocatalysts instead of heavy metals, and cutting water use with membrane filtration. A few European and U.S.-based companies now produce allopurinol with up to 90% less toxic waste. However, these methods are more expensive, so they’re not yet standard across the industry.

Does allopurinol end up in drinking water?

Yes, trace amounts have been detected in drinking water supplies in Germany, the U.S., and India. Wastewater treatment plants don’t fully remove allopurinol because it’s designed to be stable in the body - and that same stability makes it hard to break down in nature. Concentrations are low (below 0.05 micrograms per liter), but long-term effects are still being studied.

Are there greener alternatives to allopurinol?

Febuxostat is another drug used to lower uric acid, but its production has similar environmental issues. There are no widely available alternatives with significantly lower environmental impact. Research is ongoing into plant-based uric acid inhibitors, but none are approved for use yet. For now, the best option is to support manufacturers who use cleaner production methods.

Jackson Olsen

October 31, 2025So we’re just supposed to ignore the pollution because the drug saves lives? That’s not a solution, that’s a cop-out.

Penny Clark

November 1, 2025im crying thinking about the fish in those rivers 😭 i take this med for my gout and now i feel so guilty. anyone know if my pharmacy carries the green version??

Niki Tiki

November 2, 2025why do we even care what some poor country does with their waste we dont live there stop guilt tripping americans

Jim Allen

November 3, 2025so the real villain here is capitalism? or is it just humans being humans? 🤔 we all want cheap stuff. even if it kills rivers. i mean… we’re all complicit.

Nate Girard

November 4, 2025what if we started a movement to demand transparency? like a green pharma badge on bottles? we could pressure pharmacies to only stock from ethical makers. small steps, but it adds up 💪

Carolyn Kiger

November 5, 2025my dad’s on allopurinol. he’s 72. i’m not gonna tell him to stop. but i’m gonna call my pharmacist tomorrow and ask where it’s made. small act, but it matters.

krishna raut

November 6, 2025in india factories are closing because of pollution laws. new plants are using closed loops. change is coming slow but it’s coming.

Prakash pawar

November 7, 2025you think your western guilt fixes anything? we feed the world with cheap meds you take for granted. stop pretending you care about rivers when your carbon footprint is 10x ours

MOLLY SURNO

November 9, 2025It is important to acknowledge that pharmaceutical production, while necessary, often operates outside the scope of public awareness. The disconnect between consumption and consequence is systemic and requires institutional reform rather than individual guilt.

Alex Hundert

November 11, 2025if you’re not asking your pharmacist where your meds come from, you’re part of the problem. period. no more ‘i didn’t know’ excuses.