When your lungs start to stiffen like old rubber, breathing becomes a chore-not just when you’re running, but even when you’re sitting still. That’s what happens in interstitial lung disease (ILD), a group of more than 200 conditions where the tissue around your air sacs fills with scar tissue. Unlike a sprained ankle that heals, this scarring doesn’t go away. Once it builds up, your lungs lose their ability to expand and transfer oxygen into your blood. It’s not asthma. It’s not COPD. It’s something quieter, slower, and far more insidious.

How ILD Turns Healthy Lungs Into Scarred Ones

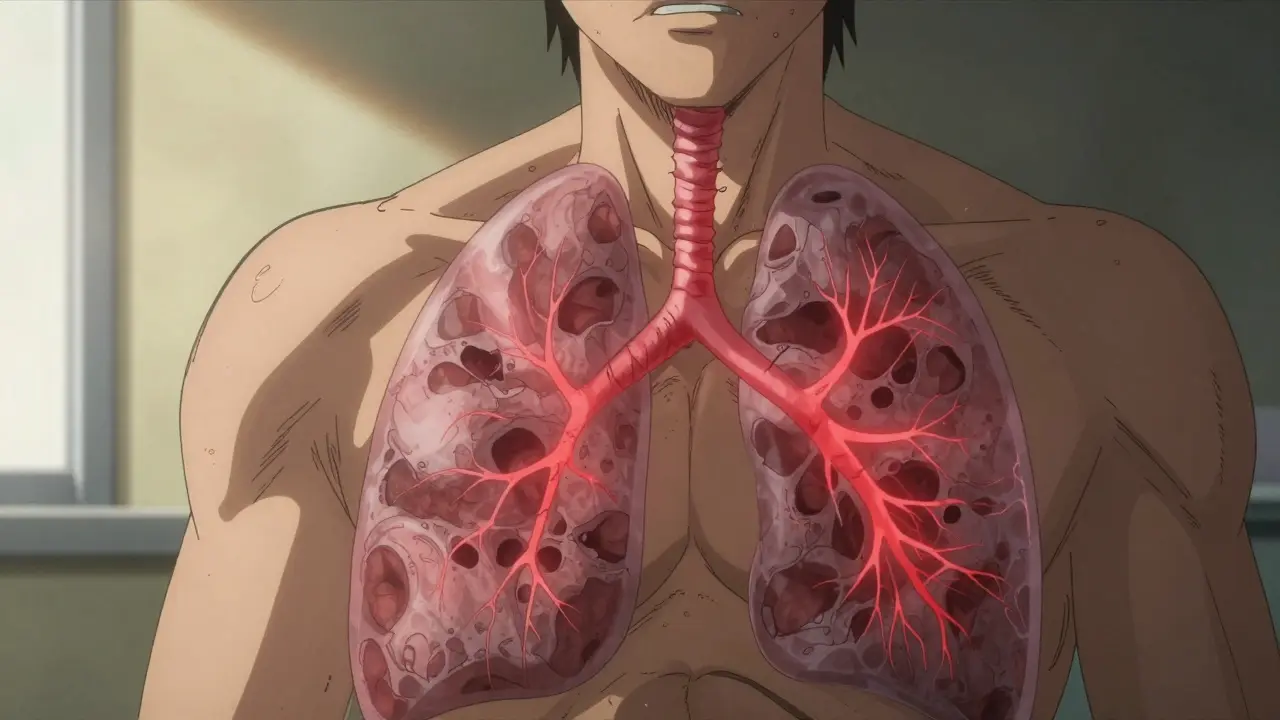

Your lungs are made of millions of tiny air sacs called alveoli, surrounded by a thin web of tissue called the interstitium. In a healthy lung, this tissue is thinner than a sheet of paper-under 0.1mm. In advanced ILD, it thickens to 1mm or more. That’s not just inflammation. That’s fibrosis. Permanent, stiff, non-functional scar tissue.This doesn’t happen overnight. Most people notice it slowly: first, getting winded climbing stairs. Then, breathing hard while washing dishes. Eventually, even talking on the phone becomes tiring. A dry cough follows-persistent, unproductive, and frustrating. Fatigue sets in like a heavy blanket. By the time many patients see a specialist, their lungs have already lost 20-50% of their capacity, measured by forced vital capacity (FVC). Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) drops by 30-60%, meaning oxygen barely makes it into the bloodstream.

The scarring doesn’t care if you’re young or old. But it does favor certain groups. People over 75 are at highest risk. Smokers, former asbestos workers, and those with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or scleroderma are more likely to develop it. And here’s the kicker: nearly 30% of ILD cases are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)-meaning no clear cause. You didn’t do anything wrong. It just happened.

The Most Common Types of ILD and How They Differ

Not all ILD is the same. Think of it like different types of cancer-same broad category, wildly different behaviors.Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) is the most common, making up 20-30% of cases. It’s relentless. Without treatment, median survival is only 3-5 years after diagnosis. FVC declines by 200-300 mL per year. It’s the one where antifibrotic drugs like pirfenidone and nintedanib actually slow the damage.

Connective Tissue Disease-Associated ILD comes from autoimmune conditions. Rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or scleroderma can trigger lung scarring. The good news? It often progresses slower than IPF. Five-year survival rates can be 70-80%. Treating the underlying autoimmune disease can help the lungs too.

Sarcoidosis is another type. In about 60-70% of cases, the body’s immune system forms tiny clumps of cells in the lungs-and then, magically, they disappear within two years. No treatment needed. But for the other 30-40%, it becomes chronic and fibrotic, requiring long-term care.

Drug-Induced ILD is often reversible. If you’ve taken amiodarone, nitrofurantoin, or some chemotherapy drugs, stopping the medication can lead to improvement within 3-6 months. Radiation-induced ILD, on the other hand, is usually permanent. It shows up 1-6 months after treatment and affects 30-50% of those who’ve had chest radiation.

And then there’s the rare, brutal ones: acute interstitial pneumonitis. It strikes fast. 60-70% of patients die within three months, even in intensive care. It’s the emergency room version of ILD.

Diagnosis: Why It Takes Over a Year

Here’s the painful truth: most people get misdiagnosed first. One patient told me they were told it was “just aging” for two years. Another was treated for asthma with inhalers that did nothing. According to patient surveys, the average person sees three doctors before getting the right diagnosis.Why? Because the symptoms mimic other common conditions. And not every doctor knows how to look for ILD.

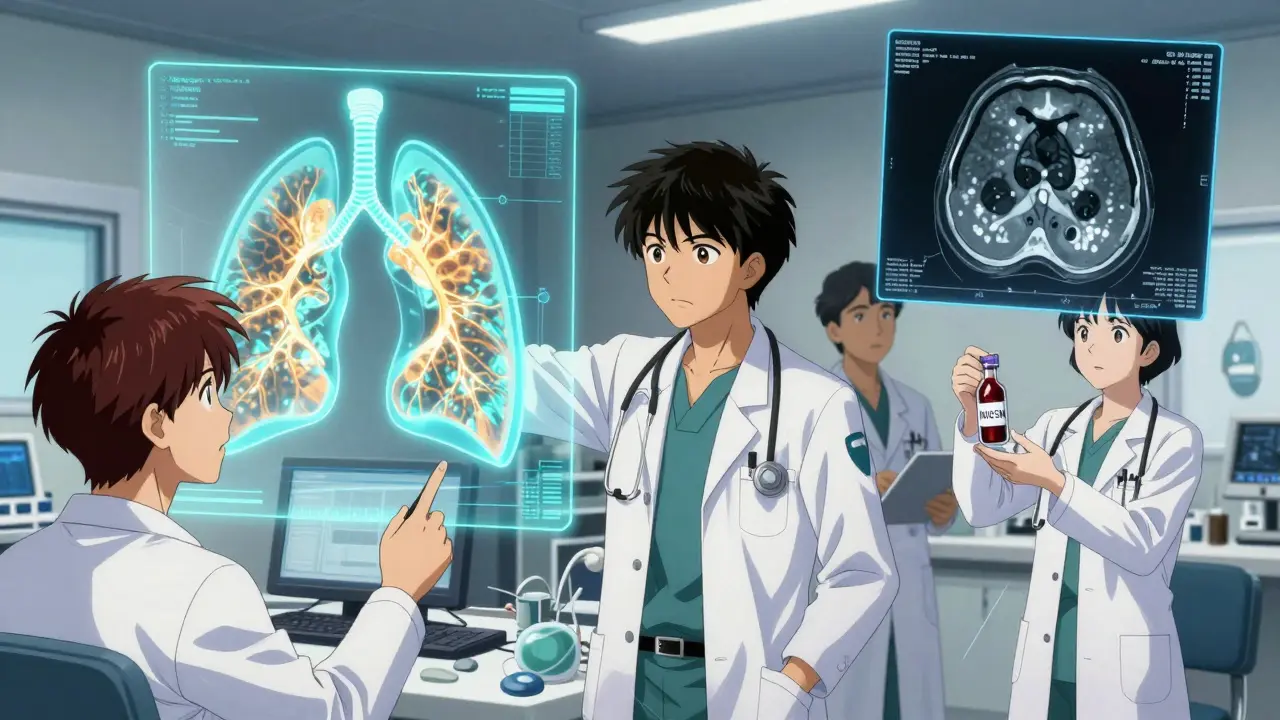

The gold standard is a high-resolution CT scan (HRCT) with 1mm slices. It shows the pattern of scarring-whether it’s honeycombing, reticular patterns, or ground-glass opacities. But even radiologists can miss early signs. One 2023 study found AI tools now detect ILD patterns with 92% accuracy, beating human experts who get it right only 78% of the time.

After the scan, a multidisciplinary team-pulmonologist, radiologist, pathologist-meets to review the case. This reduces misdiagnosis from 30% down to under 10%. But access to these teams is uneven. Academic hospitals have them. Rural clinics often don’t. That’s why diagnosis takes, on average, 11.3 months from first symptom.

There’s also a new blood test now: MUC5B promoter polymorphism testing. If you test positive, your risk of developing IPF is 85% higher. It’s not a diagnostic tool on its own, but it helps predict who’s likely to progress.

Treatment: Slowing the Scarring, Not Reversing It

There’s no cure. But there are tools to slow it down.For IPF, two drugs are FDA-approved: nintedanib (Ofev®) and pirfenidone (Esbriet®). Both reduce the rate of lung function decline by about 50% over a year. That doesn’t mean you feel better right away. It means you don’t get worse as fast. Nintedanib is taken twice daily. Pirfenidone, three times a day. Both cause side effects: nausea, diarrhea, sun sensitivity. Many patients need dose adjustments.

But here’s the catch: these drugs only work for IPF and a few other progressive fibrosing ILDs. They don’t help sarcoidosis or drug-induced cases. And they cost $9,450-$11,700 a month. Insurance often covers them, but copays can still hit $500 a month. Patient assistance programs exist, but navigating them is a full-time job.

There’s a new drug: zampilodib, approved by the FDA in September 2023. It’s the first new antifibrotic in nearly a decade. In trials, it cut FVC decline by 48% compared to placebo. It’s not a miracle, but it’s another arrow in the quiver.

For non-IPF types, treatment depends on the cause. Steroids or immunosuppressants might help if it’s autoimmune. Stopping the offending drug can reverse drug-induced ILD. In sarcoidosis, sometimes nothing at all is the best plan.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation: The Real Game-Changer

Medications don’t fix your stamina. That’s where pulmonary rehab comes in.It’s not fancy. It’s walking on a treadmill with oxygen, doing arm curls, learning breathing techniques, and getting coached on energy conservation. Most programs run 8-12 weeks, 2-3 times a week. After completion, patients gain 45-60 meters on the 6-minute walk test. That’s not just a number-it means you can walk to the mailbox without stopping. You can carry groceries. You can sit through a movie.

Seventy-two percent of patients in one UCHealth study said rehab gave them back some control. And it’s cheaper than drugs. Medicare covers it. Most private insurers do too.

It’s also where patients learn to use oxygen properly. If your resting oxygen saturation drops below 88%, you need supplemental oxygen. About 55% of IPF patients need it within two years. Learning how to manage the tank, the tubing, the alarms-this is part of survival.

Living With ILD: The Emotional and Practical Burden

The physical toll is heavy. But the emotional toll? It’s heavier.Sixty-eight percent of patients report anxiety tied to breathlessness. Forty-five percent stop going out because they need oxygen or fear collapsing in public. Caregivers spend 20+ hours a week helping-managing oxygen, lifting, driving to appointments. One wife told me she stopped watching TV because her husband couldn’t sit still long enough to finish an episode.

And then there’s the isolation. Support groups on Pulmonary Fibrosis News Forums are lifelines. People share stories of misdiagnosis, insurance battles, side effects from pirfenidone that made them vomit for weeks. But they also share wins: “I walked to the park today without stopping.” “I got my oxygen tank to fit in the car.”

There’s no shame in needing help. But there’s a lot of shame in asking for it. That’s why counseling and peer support are now part of standard care at top ILD centers.

What’s Next? Hope on the Horizon

Research is accelerating. There are 9 phase 3 trials for new antifibrotic drugs. 17 trials are testing stem cells. Scientists are looking at 14 genes linked to ILD susceptibility. The goal? Personalized medicine: match the drug to the patient’s genetic profile.Screening high-risk groups-smokers over 60, people with autoimmune disease-is now being piloted. Early detection could cut diagnosis time by 40%. Imagine catching scarring before it’s visible on a scan. That’s the future.

And AI is changing diagnostics. Algorithms can now spot early fibrosis patterns invisible to the human eye. In the next five years, we may see routine AI-assisted CT scans in primary care, catching ILD before it’s too late.

For now, the message is clear: if you’ve had unexplained shortness of breath for months, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s aging. Get a CT scan. Ask for a pulmonologist. Demand a multidisciplinary review. Because early intervention doesn’t reverse the damage-but it buys you time. And time is everything.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is interstitial lung disease the same as pulmonary fibrosis?

Pulmonary fibrosis is a type of interstitial lung disease (ILD), but not all ILD is fibrosis. ILD is the broader category that includes inflammation, scarring, and other damage to the lung’s supporting tissue. Pulmonary fibrosis specifically refers to the buildup of scar tissue. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common and aggressive form of fibrotic ILD.

Can you live a normal life with ILD?

You can live meaningfully, but not necessarily “normally.” Many people adjust by pacing activities, using oxygen, joining pulmonary rehab, and avoiding triggers like smoke or pollution. Some continue working, traveling, and spending time with family. But energy levels drop, and breathlessness limits what’s possible. The goal isn’t to return to how you were before-it’s to make the most of what you have now.

Do antifibrotic drugs like pirfenidone or nintedanib cure ILD?

No. These drugs slow the progression of lung scarring, especially in IPF and some other progressive forms. They don’t remove existing scar tissue or restore lung function. But they can reduce the rate of decline by about half over a year. That means more time without needing a lung transplant or full-time oxygen.

What causes ILD if it’s not from smoking or asbestos?

In many cases, especially with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), the cause is unknown. But research points to a mix of genetics, aging, and abnormal healing responses. Some people have gene mutations that make their lungs more prone to scarring after minor injury-even from a cold or acid reflux. Autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or lupus can also trigger ILD without any environmental exposure.

How do I know if I need oxygen therapy?

Your doctor will check your blood oxygen levels with a pulse oximeter. If your resting oxygen saturation drops below 88%, you likely need supplemental oxygen. Some people only need it during sleep or exercise. Others need it 24/7. A six-minute walk test can also help determine how much oxygen you need during activity.

Is lung transplant the only option if ILD gets worse?

For advanced ILD that doesn’t respond to other treatments, lung transplant is the only option that can restore function. But it’s not for everyone. You need to be physically strong enough to survive surgery and lifelong immunosuppression. Age, other health conditions, and emotional readiness matter. About 50% of transplant recipients live five years or more. It’s a major decision-and one best made with a specialized ILD team.

What to Do Next

If you’ve been told you have ILD, don’t panic-but don’t delay either. Find a pulmonologist who specializes in ILD. Ask if your hospital has a multidisciplinary clinic. Get a high-resolution CT scan if you haven’t already. Start pulmonary rehab. Learn about your drug options and side effects. Connect with a support group. And if you’re still unsure, get a second opinion. ILD is complex, but you’re not alone in navigating it.

If you’re a caregiver, remember: your needs matter too. Take breaks. Ask for help. Use respite services. You can’t pour from an empty cup.

And if you’re still healthy-don’t ignore persistent cough or shortness of breath. Get it checked. Early detection saves more than lungs. It saves time, independence, and life.

Jocelyn Lachapelle

December 16, 2025I was diagnosed with IPF two years ago. I thought I was done. Then I started pulmonary rehab. Now I walk my dog every morning without stopping. It’s not magic. It’s just showing up.

One day at a time.

Lisa Davies

December 16, 2025This post gave me chills 😭 I’m a caregiver for my mom with connective tissue ILD. She’s on nintedanib and does rehab twice a week. She says it’s the only thing that makes her feel like herself again. Thank you for writing this.

Nupur Vimal

December 16, 2025Most people don’t realize ILD isn’t just old people stuff. My sister was 42 when she got diagnosed after a cold that never went away. No smoking history. No asbestos. Just bad luck and a broken healing response. The MUC5B test saved us months of guessing

Cassie Henriques

December 17, 2025The 92% AI detection accuracy stat is wild. I work in radiology and we’ve been using AI-assisted HRCT for six months. The interstitial patterns we missed before-honeycombing in the basal lobes, subtle reticulation-now jump out. It’s not replacing us. It’s amplifying our eyes. But access disparities? Still a nightmare in rural areas.

Jake Sinatra

December 18, 2025I appreciate the thorough breakdown of treatment options. However, I must emphasize that while antifibrotics slow progression, they do not restore function. Patients must be counseled on realistic expectations. Pulmonary rehabilitation remains the most accessible and evidence-based intervention for quality of life improvement.

Melissa Taylor

December 19, 2025To anyone reading this and feeling alone: you’re not. I’ve been in support groups for five years. People share the small wins-like finally being able to hug their grandkid without gasping. Those moments matter more than any scan. Keep showing up. Even if it’s just to breathe.

John Brown

December 20, 2025I used to think lung disease meant you were done living. Then I met a guy in rehab who was 78, on oxygen, and still painting watercolors every day. He said, ‘I don’t need to run marathons anymore. I just need to see the sunrise.’ That stuck with me. It’s not about what you lose. It’s about what you still have.

Christina Bischof

December 21, 2025My dad had IPF. He hated the pills. The nausea was brutal. But he kept taking them because he didn’t want to miss his granddaughter’s first steps. He made it to her third birthday. That’s the kind of time these drugs buy. Not forever. But enough.