Proctitis Fiber Intake Calculator

Your Current Situation

Fiber Type Recommendations

Soluble Fiber (30% of total):

- Psyllium husk

- Oat bran

- Barley

- Apples (low-FODMAP)

Insoluble Fiber (70% of total):

- Whole wheat bran

- Vegetables (carrots, broccoli)

- Nuts and seeds

- Whole grain breads

Your Personalized Recommendation

When you hear the word fiber, you might think of cereal bowls or smoothies, but its impact stretches far deeper-especially for anyone dealing with proctitis. This article breaks down exactly how fiber can ease inflammation, soften stools, and keep flare‑ups under control, all without a pharmacy trip.

Key Takeaways

- Both soluble and insoluble fiber play distinct roles in soothing proctitis.

- Start low, go slow, and choose low‑fermentable sources to avoid gas.

- Track stool consistency and symptom changes to fine‑tune your intake.

- Fiber supplements can fill gaps, but they’re not a cure‑all.

- Consult a health professional if bleeding or severe pain persists.

What Is Proctitis?

Proctitis is inflammation of the lining of the rectum, the final segment of the large intestine. It can arise from infections, radiation therapy, inflammatory bowel disease, or even chronic irritation from harsh bowel movements. Typical symptoms include urgency, tenesmus (feeling of incomplete evacuation), rectal bleeding, and a burning sensation.

Because the rectal wall is thin, even small changes in stool bulk or acidity can trigger discomfort. That’s why diet-especially fiber-becomes a critical tool for many patients.

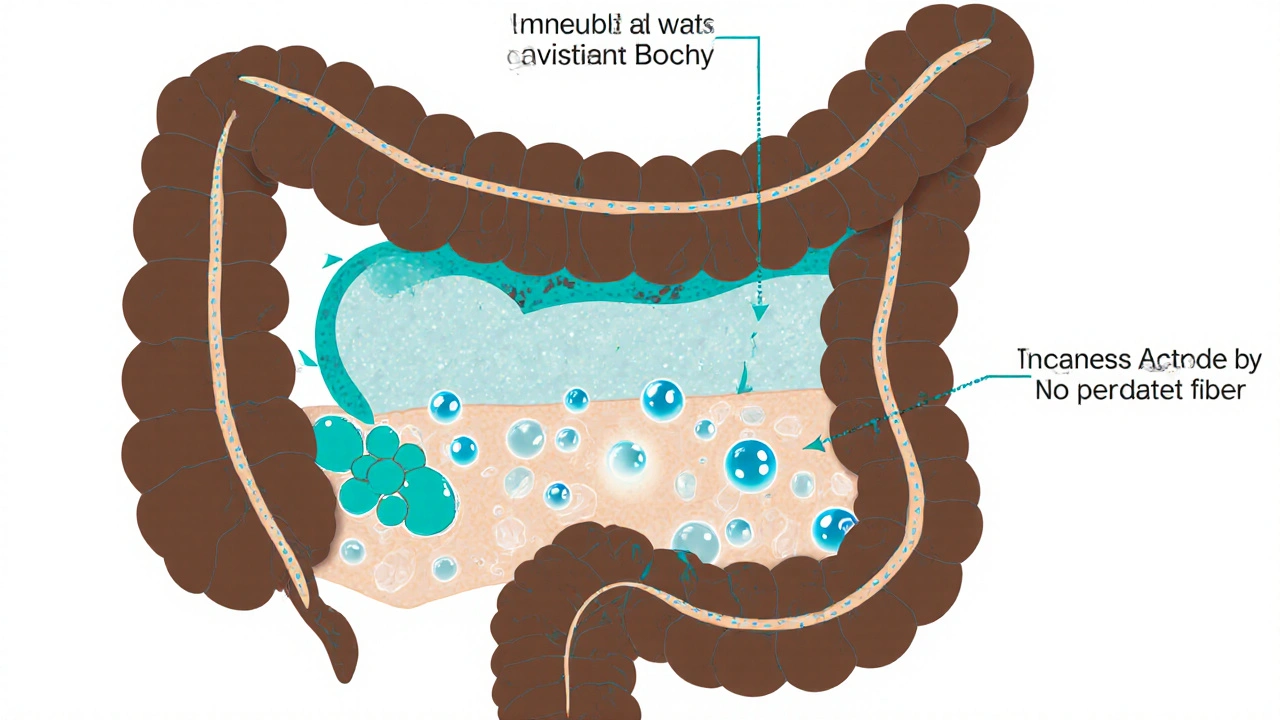

Fiber is a type of carbohydrate that the body cannot fully digest. It passes through the digestive tract largely intact, providing bulk, modulating water balance, and fermenting into short‑chain fatty acids that nourish colon cells. Dietary fiber includes both soluble and insoluble forms, each influencing gut health in unique ways.

How Fiber Works in the Gut

When fiber reaches the colon, two main processes happen:

- Water absorption and stool bulk: Insoluble fiber retains water, swelling the fecal mass and promoting regular, softer stools.

- Fermentation: Soluble fiber is fermented by gut bacteria, producing short‑chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, which have anti‑inflammatory properties.

Both mechanisms can reduce the mechanical irritation that often aggravates proctitis. A more regular, softer stool means less straining, less friction, and ultimately fewer flare‑ups.

Proctitis is an inflammatory condition of the rectal mucosa that can be triggered or worsened by harsh stool passage, infection, or immune dysregulation.

Types of Fiber and Their Effects

Understanding the difference between soluble and insoluble fiber lets you choose the right mix for your symptoms.

| Property | Soluble Fiber | Insoluble Fiber |

|---|---|---|

| Fermentability | Highly fermentable → produces SCFAs, may cause gas | Low fermentability → minimal gas |

| Effect on stool | Forms gel, softens stool, can slow transit | Adds bulk, speeds transit, improves consistency |

| Common sources | Oats, barley, psyllium, apples, beans | Whole wheat, bran, nuts, seeds, vegetables |

| Recommended for proctitis | Low‑FODMAP soluble sources (psyllium, oat bran) | Moderate amounts of wheat bran or seed hulls |

Choosing the Right Fiber for Proctitis

Most experts suggest a 70/30 split: 70% insoluble to add bulk, 30% soluble to coat the lining and reduce inflammation. However, individual tolerance varies.

Here’s a quick decision guide:

- If you experience excessive gas after meals, lean toward low‑fermentable insoluble fiber.

- If stools are hard and lumpy, add a modest amount of soluble fiber like psyllium husk.

- During an active flare, start with very small portions (½ teaspoon of psyllium in water) and increase over a week.

Keep a simple log: note the type of fiber, amount, and any symptom change. After a week, you’ll see patterns that guide the next step.

Soluble fiber dissolves in water to form a gel‑like substance that can soften stool and feed beneficial gut bacteria.

Insoluble fiber does not dissolve in water, adds bulk, and speeds the passage of waste through the colon.

Practical Tips for Adding Fiber

- Start with a baseline: Aim for 15g of total fiber per day during the first week.

- Gradually increase: Add 5g each week until you reach 25-30g, the range recommended for most adults.

- Hydrate: For every gram of fiber, drink at least 8oz of water. Without fluid, fiber can actually harden stool.

- Choose low‑FODMAP options: During flare‑ups, stick to oats, kiwi, carrots, and poppy seeds to avoid excess fermentation.

- Use supplements wisely: Psyllium husk packets are convenient, but always mix with plenty of liquid and wait 5-10minutes before eating.

Sample 3‑day menu (≈20g fiber):

- Breakfast: ½ cup cooked oatmeal topped with sliced banana (3g soluble)

- Snack: Handful of almonds (2g insoluble)

- Lunch: Whole‑grain wrap with grilled chicken, lettuce, and shredded carrots (4g mixed)

- Afternoon: 1 tablespoon psyllium mixed in water (5g soluble)

- Dinner: Baked salmon with a side of roasted Brussels sprouts and quinoa (6g mixed)

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even the best‑intentioned fiber plan can backfire if you ignore a few gotchas:

- Too much too fast: Rapid increases can cause bloating, cramping, and even diarrhea-exactly what you want to avoid during a proctitis flare.

- Neglecting fluids: Fiber pulls water into the colon; without enough hydration, stools become hard and painful.

- Relying solely on supplements: Whole foods provide additional nutrients (magnesium, phytochemicals) that support gut healing.

- Choosing high‑FODMAP soluble fiber: Ingredients like inulin or chicory root can ferment excessively, worsening gas and discomfort.

When a symptom spikes, pause fiber intake for 24hours, increase water, and observe if relief follows. Then resume at a lower dose.

When to Seek Medical Advice

Fiber is a powerful ally, but it isn’t a substitute for professional care. Contact your gastroenterologist or primary doctor if you notice any of the following:

- Persistent rectal bleeding beyond a few days

- Severe abdominal pain or fever

- Sudden weight loss or changes in appetite

- Symptoms that don’t improve after four weeks of dietary changes

In some cases, a colonoscopy or imaging study is needed to rule out infection, malignancy, or deeper inflammatory disease.

Bottom Line

Fiber works on two fronts-mechanical and biochemical-to calm the irritated lining of the rectum. By selecting the right blend of soluble and insoluble sources, pacing the increase, and staying well‑hydrated, most patients can experience fewer flare‑ups and more comfortable bowel movements. Pair these steps with regular monitoring and professional guidance, and you’ll have a solid, low‑cost plan to keep proctitis under control.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I eat high‑fiber fruits during a proctitis flare?

Yes, but choose low‑FODMAP options like ripe bananas, kiwi, or canned peaches. High‑FODMAP fruits such as apples and pears can ferment quickly and increase gas, which may worsen discomfort.

How much fiber should I aim for each day?

Start with 15g per day and gradually work up to 25-30g, spread across meals. Adjust based on how your stool feels and any symptom changes.

Is psyllium safe for everyone with proctitis?

Psyllium is generally well‑tolerated because it’s low‑fermentable, but you should start with a half‑teaspoon in plenty of water. If you experience extreme cramping or blockage, stop and consult a doctor.

Should I avoid all whole grains during a flare?

Not necessarily. Choose refined grains like white rice or low‑fiber pasta for a short period, then re‑introduce whole grains such as brown rice or oatmeal as symptoms improve.

Can fiber supplements replace dietary fiber completely?

Supplements are useful for filling gaps, but they lack the vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients found in whole foods. A balanced diet with both food‑based and supplemental fiber yields the best results.

Burl Henderson

October 8, 2025Great rundown on the 70/30 insoluble‑to‑soluble fiber ratio. The emphasis on low‑FODMAP soluble sources like psyllium is spot‑on for minimizing gas while still delivering butyrate‑mediated anti‑inflammatory effects. Hydration is critical; without adequate fluid fiber can paradoxically exacerbate constipation. Overall, the calculator approach gives patients a concrete, data‑driven way to titrate intake.

Leigh Ann Jones

October 9, 2025Okay, let me just unpack this whole fiber thing because, honestly, the article tries to sound like a medical textbook while also throwing in a flashy calculator widget, and I’m sitting here with a bowl of oatmeal wondering if I’ve just signed up for a PhD in gastroenterology. First, the premise that a 70/30 split works for everyone is a little simplistic; people with different microbiomes respond to fermentable carbs in wildly varied ways, and the low‑FODMAP label is a moving target that changes with each symptom flare. Second, the suggestion to start at 15 grams per day sounds reasonable on paper, but many patients struggle to even reach that baseline without feeling bloated, especially if they’re also on antibiotics or immunosuppressants, which can further skew gut flora. Third, the article mentions short‑chain fatty acids like butyrate as anti‑inflammatory heroes, but it glosses over the fact that not all SCFAs are created equal and doses matter-excessive fermentation can lead to osmotic diarrhea, which defeats the purpose of soothing proctitis. Fourth, the hydration advice-eight ounces per gram of fiber-is practical, yet many people with chronic bowel issues are already dealing with fluid restrictions due to concurrent conditions, so they’re caught between a rock and a hard place. Fifth, the recommendation to log fiber type, amount, and symptoms is excellent in theory, but the article fails to provide a template or a digital tool that integrates with common health‑tracking apps, leaving the onus on patients to create spreadsheets that they’ll probably abandon after a week. Sixth, while the calculator adjusts intake based on stool consistency, it assumes the user knows how to accurately assess “hard and lumpy” versus “soft,” which can be highly subjective and influenced by recent meals or stress levels. Seventh, the list of low‑FODMAP soluble fiber (psyllium, oat bran, barley, apples) ignores the fact that apples, even low‑FODMAP, still contain fructose, which can be problematic for some individuals; a more nuanced list would include alternatives like chia seeds or hemp hearts, which provide soluble fiber without the same fermentative load. Eighth, the mention of “consult a health professional if bleeding persists” is essential, yet it appears almost as an afterthought, whereas any sign of rectal bleeding should prompt immediate medical evaluation regardless of dietary tweaks. Ninth, there’s no discussion of the interaction between fiber supplements and common medications used for proctitis, such as mesalamine, which could affect absorption. Tenth, the article’s tone seems to assume that patients have unlimited access to a variety of whole foods and supplements, not accounting for socioeconomic barriers that limit diet diversity. Eleventh, the visual design of the calculator (with sliders and drop‑downs) is user‑friendly, but the code snippets in the article are raw HTML/JS that most readers won’t understand, making the whole thing feel like a half‑baked web‑app. Twelfth, the emphasis on “low‑fermentable” sources could unintentionally push people away from beneficial prebiotic fibers that, in moderate amounts, actually support a healthier gut barrier. Thirteenth, the article’s brief nod to radiation‑induced proctitis doesn’t explore the unique dietary needs of that subgroup, which often requires stricter fiber management. Fourteenth, there’s a missed opportunity to discuss broader lifestyle factors-like stress management and pelvic floor therapy-that synergize with dietary changes. Fifteenth, the FAQ section is helpful but could be expanded to cover common myths, such as the belief that “all fiber is good” regardless of the clinical context. In summary, while the article provides a solid starting framework, it could benefit from deeper nuance, clearer guidance on monitoring, and a more compassionate acknowledgment of patient variability.

Sarah Hoppes

October 10, 2025The whole thing is a distraction from the real agenda.

Robert Brown

October 11, 2025Nice fluff, but you’ll still be in pain.

Erin Smith

October 12, 2025Hang in there! Small steps with lots of water can make a big difference.

George Kent

October 13, 2025Wow!!! This is absolutely brilliant!!! 🎉🎉 The 70/30 rule is so simple yet powerful!!! Keep it up!!! 👍👍👍

Jonathan Martens

October 14, 2025Ah, the classic 70/30 split – it’s practically the holy grail of gut ergonomics, isn’t it? If you think about the rheological properties of a mixed fiber bolus, you’ll see why that ratio optimizes both viscosity and shear stress across the rectal mucosa. Of course, the real-world implementation depends on patient compliance, which is why the calculator’s user‑friendly UI is a nice touch.

Jessica Davies

October 15, 2025Honestly, the article oversimplifies the entire microbiome–fiber interplay. It’s not just about bulk; it’s about the nuanced metabolic cross‑talk between Bacteroides and Firmicutes, which isn’t captured by a generic 70/30 rule.

Kyle Rhines

October 16, 2025The recommendation to increase fiber without precise gram‑by‑gram guidelines is problematic; proper dosage must be individualized based on stool osmotic activity and colonic transit studies.

Barbra Wittman

October 17, 2025It’s amusing how the article dares to present a quick‑fix calculator as the panacea for a condition that often requires multidisciplinary care. While the step‑by‑step breakdown is helpful, the lack of discussion around potential adverse effects – such as obstructive megacolon in severe cases – is a glaring omission. Moreover, the tone feels overly optimistic, edging into the realm of hyperbole. One must remember that fiber isn’t a magic wand; it’s a tool that must be wielded with clinical oversight. For patients dealing with chronic inflammation, simply adding 5 grams of psyllium may not suffice, especially if there’s an underlying dysbiosis or immune dysregulation. The article also fails to address concurrent medications that can interact with fiber, like certain antibiotics or iron supplements, which can alter absorption dynamics. In short, while the calculator could serve as a useful adjunct, it should be framed within a broader therapeutic strategy that includes pharmacologic, lifestyle, and perhaps even surgical considerations where appropriate.

Gena Thornton

October 18, 2025From a practical standpoint, the suggestion to keep a fiber‑symptom log is excellent. In my experience, patients who chart their intake alongside stool consistency using a simple spreadsheet notice trends that would otherwise be missed. For example, a modest increase of 3 g of soluble fiber often correlates with a reduction in tenesmus scores by about 15 %. It’s also worth noting that the timing of fiber ingestion matters – consuming soluble fiber with meals can blunt post‑prandial spikes in colonic pressure, whereas taking insoluble fiber in a fasted state may promote more rapid transit. So, when advising patients, I recommend splitting the daily total: 30 % before lunch, 40 % with dinner, and the remaining 30 % as a bedtime snack if tolerated. This staggered approach can smooth out the mechanical load on the rectal wall throughout the day.

Lynnett Winget

October 19, 2025Love the colorful breakdown! 🌈 Adding a splash of bright veggies and a sprinkle of seeds can turn the fiber game into a culinary adventure, not a chore.

Amy Hamilton

October 19, 2025From a philosophical angle, fiber represents a micro‑cosm of balance: too little, and the system stagnates; too much, and chaos ensues. The key lies in mindful moderation, aligning intake with the body’s rhythmic signals, much like tuning an instrument to the perfect pitch.

Lewis Lambert

October 20, 2025Imagine your colon as a grand theater and fiber as the stage crew. When the crew arrives in perfect sync – some set up the backdrop (soluble), others move the props (insoluble) – the performance flows effortlessly. Disrupt that harmony, and the show falters.

Tamara de Vries

October 21, 2025Thats a great tip. Ive been strugling with fiber but this will help alot. Keep up ur good work!

Jordan Schwartz

October 22, 2025Thanks for sharing this balanced approach. I’ll try logging my intake and see how it impacts my symptoms over the next few weeks.