When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But behind every generic pill is a rigorous, science-backed process that proves it works exactly like the original. That process is called a bioequivalence study. These aren’t just lab tests-they’re controlled human trials designed to show that the generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same speed as the brand-name drug. If it doesn’t pass, it doesn’t get approved.

Why Bioequivalence Studies Exist

Before 1984, companies had to run full clinical trials to prove a generic drug was safe and effective. That meant spending millions and waiting years. The Hatch-Waxman Act changed that. It said: if you can prove your drug behaves the same way in the body as the original, you don’t need to repeat every clinical trial. That’s where bioequivalence studies come in. They’re the shortcut that lets safe, effective generics reach patients faster and cheaper. The FDA estimates these generics saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.6 trillion between 2010 and 2019.Regulators like the FDA, EMA, and Japan’s PMDA all require bioequivalence data before approving a generic. The goal isn’t to find something slightly similar-it’s to prove the two drugs are therapeutically identical. For most drugs, that means matching two key numbers: how much of the drug gets into your blood (AUC) and how fast it gets there (Cmax).

The Standard Study Design: Crossover Trials

Most bioequivalence studies use a crossover design. That means each volunteer takes both the generic (test) and brand-name (reference) drugs-just at different times. Usually, 24 to 32 healthy adults participate. They’re split into two groups. One group takes the generic first, then the brand after a break. The other group does the opposite. This helps cancel out individual differences in metabolism.The break between doses? At least five half-lives of the drug. For example, if the drug clears out in 12 hours, volunteers wait at least 60 hours before switching. This ensures no leftover drug from the first dose interferes with the second. Skipping this step is one of the most common reasons studies fail-45% of rejected applications have inadequate washout periods, according to the FDA.

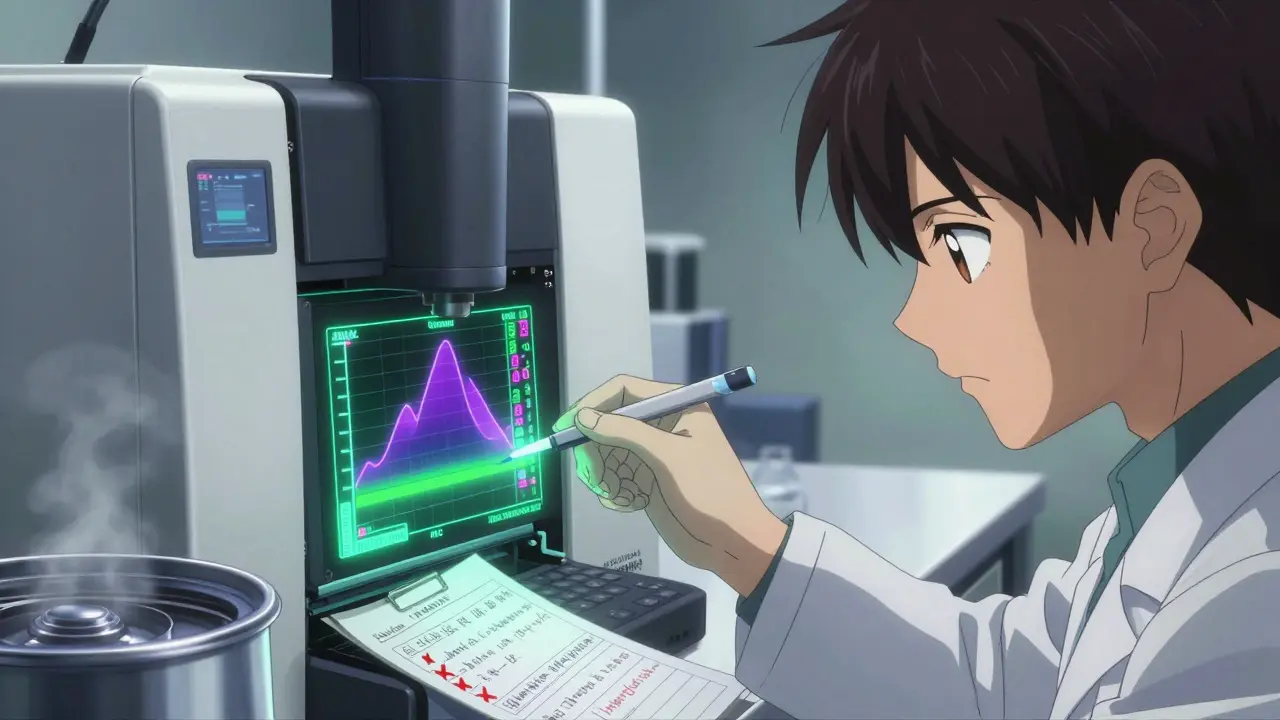

How Blood Samples Are Collected

Right before each dose, a baseline blood sample is taken. Then, volunteers give blood at specific times after taking the drug. The schedule isn’t random-it’s calculated based on how the drug behaves in the body. Typically, samples are drawn at least seven times: before dosing, just before the peak concentration (Cmax), two points around the peak, and three during the elimination phase. Sampling continues until the area under the curve (AUC) captures at least 80% of the total drug exposure.The blood is spun down to get plasma, then analyzed using LC-MS/MS-liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry. This method is precise, detecting drug levels down to nanograms per milliliter. The lab must validate its method to ensure accuracy within ±15% (±20% at the lowest detectable level). If the method isn’t solid, the whole study gets thrown out. About 22% of studies face delays because of analytical issues, costing an average of $187,000 each.

What’s Measured: Cmax and AUC

Two numbers determine if the drugs are equivalent:- Cmax: The highest concentration of the drug in the blood. This tells you how fast the drug is absorbed.

- AUC(0-t): The total drug exposure over time, from dosing until the last measurable concentration. AUC(0-∞) is used if the full elimination curve is captured.

These values are log-transformed because drug concentrations don’t follow a normal distribution. Then, a statistical test called ANOVA is run, with factors for sequence, period, treatment, and subject. The result? A 90% confidence interval for the ratio of test to reference drug.

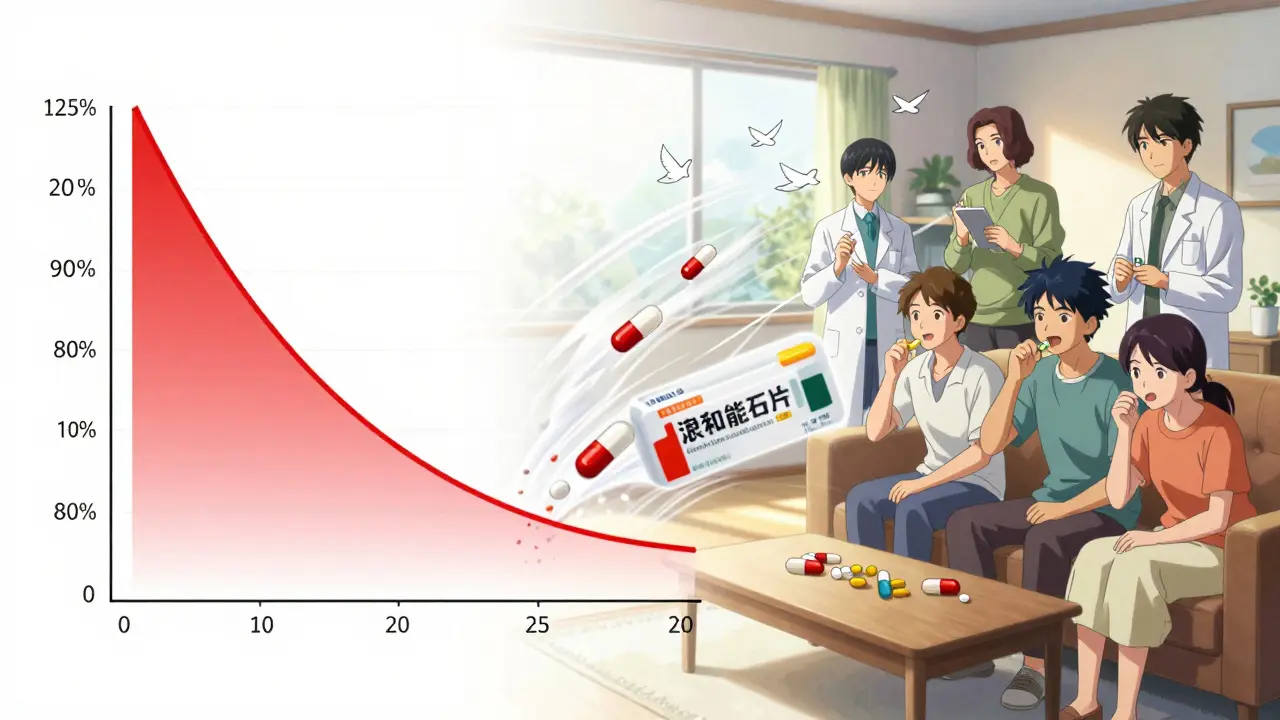

The Pass/Fail Rule: 80%-125%

Here’s the golden rule: for most drugs, the 90% confidence interval for both Cmax and AUC must fall between 80.00% and 125.00%. That means the generic’s exposure can’t be more than 25% higher or 20% lower than the brand. If it’s outside that range, the study fails.There’s an exception for narrow therapeutic index drugs-medications where even small changes can cause harm, like warfarin or levothyroxine. For these, the acceptable range tightens to 90.00%-111.11%. The FDA introduced this in 2019 after cases showed even slight differences led to clinical issues.

When the Standard Doesn’t Work

Not all drugs fit the standard crossover model. Some have very long half-lives-like 72 hours or more. Waiting five half-lives means volunteers would need to stay in a clinic for over two weeks. That’s impractical and increases dropout risk. For these, a parallel design is used: one group gets the generic, another gets the brand. But you need more people-often 50 to 100-to make up for the lack of within-subject comparison.For extended-release pills, a multiple-dose study may be required. Instead of one dose, volunteers take the drug daily for several days. This shows whether the drug builds up properly and maintains steady levels over time.

Some drugs don’t even need blood tests. If a drug is highly soluble and rapidly absorbed (BCS Class I), regulators may approve it based on dissolution testing alone. The generic must dissolve at least 85% in the same way as the brand across pH levels 1.2 to 6.8. The similarity factor (f2) must be above 50. This is called a biowaiver. In 2022, 27% of approved generics got through this route.

What Makes or Breaks a Study

Success isn’t just about following the rules. It’s about avoiding common traps. Experts say pilot studies are non-negotiable. A small-scale test with 6-12 people helps predict how variable the drug will be in the full study. If you skip this, your main study might fail. One contract research organization reported pilot studies cut failure rates from 35% to under 10%.Another pitfall? Choosing the wrong reference product. Regulators require using a single batch of the brand-name drug, ideally from the middle-performing lot of three. If you pick a batch that dissolves too fast or too slow, your generic won’t match. Also, the test product must come from a commercial-scale batch-100,000 units or 1/10th of full production, whichever is larger.

Statistical errors are another big issue. Using the wrong model, misapplying log transformation, or not accounting for carryover effects can invalidate results. About 25% of failed studies fall into this category.

Real-World Outcomes

Some generics sail through. Teva’s generic version of Januvio (sitagliptin) got approved after just one successful study with 36 subjects. Others get rejected. Alembic’s attempt at a generic version of Trulicity failed because Cmax values varied too much across studies. That’s not because the drug was unsafe-it just didn’t consistently match the brand’s behavior.Even after approval, real-world data matters. The FDA reviewed over 1,200 bioequivalence-approved generics in 2023 and found no safety signals linked to the approval method. That’s why regulators still trust this system.

What’s Changing in Bioequivalence

The field is evolving. Modeling and simulation-like PBPK (physiologically based pharmacokinetic) models-are being used more. These computer simulations predict how a drug behaves in different people, reducing the need for human trials. Since 2020, their use has grown 35%.Regulators are also working on better rules for complex products: inhalers, topical creams, injectables. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance covers 1,500 drug substances, and the EMA is refining rules for highly variable drugs. Japan’s PMDA still requires extra dissolution tests for some products, showing global standards aren’t fully aligned.

The long-term goal? Reduce study requirements for simple generics using real-world evidence. The FDA’s 2024-2028 plan aims to cut bioequivalence study needs by 30% for certain drugs. But for now, the crossover trial with Cmax and AUC remains the gold standard.

Are bioequivalence studies safe for participants?

Yes. Bioequivalence studies use healthy volunteers who are closely monitored in clinical settings. All studies follow strict ethical guidelines and are reviewed by independent ethics committees. Participants are screened for health conditions, given detailed information about risks, and can withdraw at any time. The doses used are therapeutic, not toxic, and are based on the brand-name drug’s approved dosage.

Why do some generic drugs seem to work differently than the brand?

If a patient feels a difference, it’s rarely because the generic failed bioequivalence. More often, it’s due to psychological expectations, minor formulation differences (like fillers or coatings), or changes in how the body responds over time. Bioequivalence studies are designed to detect clinically meaningful differences-and they’re very good at it. The FDA and other agencies have found no consistent evidence that approved generics are less effective or safe.

How long does a bioequivalence study take?

It depends on the drug. For a drug with a short half-life, the study might take 2-3 weeks per volunteer: one dose, a washout period, then the second dose. For drugs with long half-lives, it can stretch to 4-6 weeks. The entire process-from protocol design to final report-usually takes 12 to 18 months. Regulatory review adds another 8-12 months on average.

Can a bioequivalence study be done without human volunteers?

Only in rare cases. For highly soluble, rapidly absorbed drugs (BCS Class I), regulators may allow a biowaiver based on dissolution testing alone. But for most systemic drugs-especially those with complex release patterns, low solubility, or narrow therapeutic windows-human data is required. Animal or in vitro data alone isn’t accepted for approval.

What happens if a bioequivalence study fails?

If the study fails, the company must figure out why. Was it the formulation? The analytical method? The sampling schedule? They may tweak the drug’s ingredients, change the manufacturing process, or redesign the study. Then they run another trial. Failure isn’t the end-it’s part of the process. Many successful generics went through multiple failed attempts before getting approved.

Allen Ye

January 5, 2026It’s fascinating how we’ve turned something as intimate as the human body’s response to a molecule into a statistical dance between 80% and 125%. We’re not just measuring drug levels-we’re measuring trust. Trust that a pill made in a factory in India, under different lighting, by different hands, with different filler grains, can do the exact same thing as the one made in New Jersey with the same brand logo on it. And yet, the data says yes. The math says yes. The FDA says yes. But our brains? Our brains still whisper, ‘But is it really the same?’ That’s not science-it’s psychology. And maybe that’s the real barrier to generic adoption, not the bioequivalence study itself.

Every time I take a generic, I think of the volunteer who gave blood 17 times in 21 days, hooked to IVs, fasting, lying still while their body became a data point. No one knows their name. No one thanks them. But they’re the reason your insulin costs $30 instead of $300. We treat bioequivalence like a regulatory checkbox, but it’s really a silent social contract between the sick, the poor, and the pharmaceutical industry. And it’s working.

Still, I wonder: if we ever moved to PBPK models exclusively, would we lose something essential? The human element? The visceral, biological proof that a drug works in flesh and blood, not just in a computer simulation? Maybe that’s why regulators still cling to crossover trials-even when they’re expensive, slow, and ethically gray. We need to see it happen in people. Not just predict it.

And yet… we’re already there. In 2022, nearly a third of generics were approved without a single human subject. That’s the future. A future where your medicine is validated by algorithms, not blood draws. I’m not sure if that’s progress or surrender.

Roshan Aryal

January 6, 2026Let me tell you something about these so-called bioequivalence studies-they’re a joke dressed up in lab coats. The FDA lets Indian and Chinese manufacturers submit data from labs that wouldn’t pass a high school science fair. I’ve seen the reports-same Cmax values, same AUC curves, all perfectly aligned like they were copied from a template. Meanwhile, real patients report differences. I’ve had patients on generic metformin who went from stable HbA1c to diabetic ketoacidosis. Coincidence? Or is the 80-125% range just a loophole for corporations to cut corners and call it science?

And don’t get me started on biowaivers. You’re telling me a pill that dissolves 85% in pH 1.2 is ‘equivalent’ to one that dissolves 87%? That’s not equivalence-that’s wishful thinking. The real problem? Western regulators are too desperate to cut costs to care about real-world outcomes. Meanwhile, the patients pay the price in side effects, hospital visits, and lost trust. This isn’t innovation. It’s exploitation dressed up as efficiency.

Jack Wernet

January 6, 2026Thank you for this exceptionally clear and thorough breakdown of the bioequivalence process. As someone who works in clinical pharmacology, I appreciate the precision with which you’ve outlined the regulatory framework, the statistical thresholds, and the practical challenges-particularly the emphasis on washout periods and analytical validation. It’s easy for the public to misunderstand generic drugs as ‘inferior,’ when in reality, the approval pathway is among the most rigorously scrutinized in all of medicine.

The 90% confidence interval requirement is not arbitrary; it’s rooted in decades of pharmacokinetic research and clinical outcome data. The fact that the FDA has found no safety signals across 1,200 approved generics speaks volumes. I would encourage patients who perceive differences to report them through MedWatch-not to dismiss generics, but to ensure the system remains responsive to real-world variability. Science is not infallible, but it is self-correcting-and this system, despite its complexity, works remarkably well.

Catherine HARDY

January 6, 2026Have you ever wondered who owns the blood samples? I mean, really-your plasma, your data, your body’s response to a drug… it’s all collected, stored, and then sold to the company that makes the brand drug. They use it to tweak their own formulations, patent new delivery systems, and extend their monopolies. The volunteers think they’re helping science. But they’re actually feeding the machine that keeps brand-name drugs expensive. And the FDA? They’re okay with it because it keeps the system ‘efficient.’

And what about the reference product? You said they pick the ‘middle-performing lot’? That’s not random-that’s cherry-picking. They pick the one that makes the generic look good. If the brand’s best batch is 120% bioavailable, and the generic matches it? That’s not equivalence. That’s manipulation.

And don’t even get me started on the fact that the FDA doesn’t re-test generics after approval. Once it’s approved, it’s never checked again. Not even once. So if the manufacturer switches suppliers, changes the coating, or tweaks the binder? No one knows. The system is built on blind faith. And that’s terrifying.

Vicki Yuan

January 7, 2026This is one of the most important topics in modern healthcare-and you explained it beautifully. I’ve spent years working in patient advocacy, and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had to reassure people that generics aren’t ‘cheap knockoffs’-they’re scientifically validated, life-saving alternatives. The fact that we’ve saved $1.6 trillion since 2010? That’s not just a number-it’s millions of people who could afford their insulin, their blood pressure meds, their antidepressants.

I especially appreciate the detail on narrow therapeutic index drugs. Many people don’t realize that warfarin and levothyroxine require tighter standards-and that’s because real people have been harmed. The system learned from its mistakes. That’s why I trust it.

Also, kudos for mentioning the volunteers. They’re the unsung heroes. I’d love to see a public campaign to recognize them. Imagine if every generic pill came with a QR code linking to a thank-you note from a real person who gave blood for you. That would change the narrative.

melissa cucic

January 7, 2026It’s remarkable, isn’t it?-how a single, seemingly technical metric-AUC(0-t), log-transformed, analyzed via ANOVA, with a 90% confidence interval falling between 80.00% and 125.00%-can determine whether a person in rural Ohio can afford their medication… or not. And yet, this is the entire foundation of modern pharmaceutical equity. No grand speeches. No political debates. Just math. Just data. Just statistical rigor.

And still, we question it. We distrust it. We whisper about ‘inactive ingredients’ and ‘fillers’ as if they’re some kind of secret sabotage. But the science is clear: the active ingredient is what matters. The rest? It’s just delivery. And if the delivery system changes slightly-say, a different binder or coating-it doesn’t change the outcome, as long as the dissolution profile and pharmacokinetics remain within bounds.

What’s truly remarkable is that this system, born out of the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984, has held up for nearly four decades. It’s not perfect-but it’s functional. And in a world of chaos, that’s more than most things can claim.

Still, I wonder: when we start replacing human trials with PBPK models… will we lose the humility that comes from seeing a drug work in a living body? Or will we simply evolve?

Akshaya Gandra _ Student - EastCaryMS

January 8, 2026this is so cool i had no idea generics had to go through all this

en Max

January 9, 2026From a pharmacokinetic methodology standpoint, the crossover design remains the gold standard due to its inherent reduction of inter-subject variability through within-subject comparison. The requirement for a washout period exceeding five half-lives is grounded in first-order elimination kinetics, ensuring negligible carryover effects-critical for accurate estimation of Cmax and AUC.

Furthermore, the use of LC-MS/MS for quantification provides the necessary sensitivity (LOQ typically <1 ng/mL) and specificity to resolve low-concentration analytes in complex biological matrices. Validation per ICH Q2(R1) guidelines ensures accuracy, precision, linearity, and robustness-parameters that, when inadequately demonstrated, contribute significantly to study rejection rates.

It’s also worth noting that the 80–125% confidence interval is derived from the log-normal distribution of pharmacokinetic parameters and is calibrated to detect clinically insignificant differences. The tighter 90–111.11% range for NTIDs reflects a risk-based regulatory approach informed by post-marketing surveillance data.

While emerging tools like PBPK modeling offer promise, they currently serve as adjuncts-not replacements-for empirical human data in systemic drug approval pathways.

Angie Rehe

January 11, 2026Okay, but here’s the real question: if a generic passes bioequivalence, why do I still get different side effects? I’ve been on the same generic for three years-then suddenly, I get migraines and nausea. I switched back to brand, and it vanished. Coincidence? Or did the manufacturer change the coating without telling anyone? And why does the FDA allow that? They don’t monitor post-approval changes. They don’t require re-testing. That’s not oversight-that’s negligence. You think this system is safe? It’s a black box. And we’re all just guessing what’s inside the pill we swallow every day.

Someone needs to audit the manufacturers. Someone needs to track batch numbers. Someone needs to stop pretending this is science when it’s just corporate convenience wrapped in a lab coat.